by Michele Larrow, Regional Co-Coordinator

It was now the middle of June, and the weather fine; and Mrs. Elton was growing impatient to name the day [for Box Hill], and settle with Mr. Weston as to pigeon-pies and cold lamb, when a lame carriage-horse threw every thing into sad uncertainty. . . .

“Is not this most vexatious, Knightley?” she cried.—”And such weather for exploring!” . . .

“You had better explore to Donwell,” replied Mr. Knightley. “That may be done without horses. Come, and eat my strawberries. They are ripening fast.”

If Mr. Knightley did not begin seriously, he was obliged to proceed so, for his proposal was caught at with delight; and the “Oh! I should like it of all things,” was not plainer in words than manner. Donwell was famous for its strawberry-beds, which seemed a plea for the invitation: but no plea was necessary; cabbage-beds would have been enough to tempt the lady, who only wanted to be going somewhere.”

Jane Austen, Emma, Vol III, Chap 6, 398-399

Mr. Knightley hosts the strawberry picking party at Donwell Abbey “at almost Midsummer” (E III, 6, 404; June 24 in the English quarter system). After the strawberries are picked and to escape Mrs. Elton, Jane Fairfax asks Mr. Knightley to show them “all the gardens . . . the whole extent.” (III, 6, 408). Contemporary Austen readers would have a sense of what the gardens would look like, both the kitchen garden (where the strawberry beds would be) and orchards and the “pleasure grounds”, which at Donwell terminate in the “broad short avenue of limes” (III, 6, 408; “lime trees” are lindens in the United States). The pleasure grounds include flower gardens, shrubbery, and wooded areas and will be discussed in the next blog. This blog will explore how a kitchen garden and orchards would be set up in the early 1800s, what plants would be growing there, and what work would be going on in them in the busy month of June.

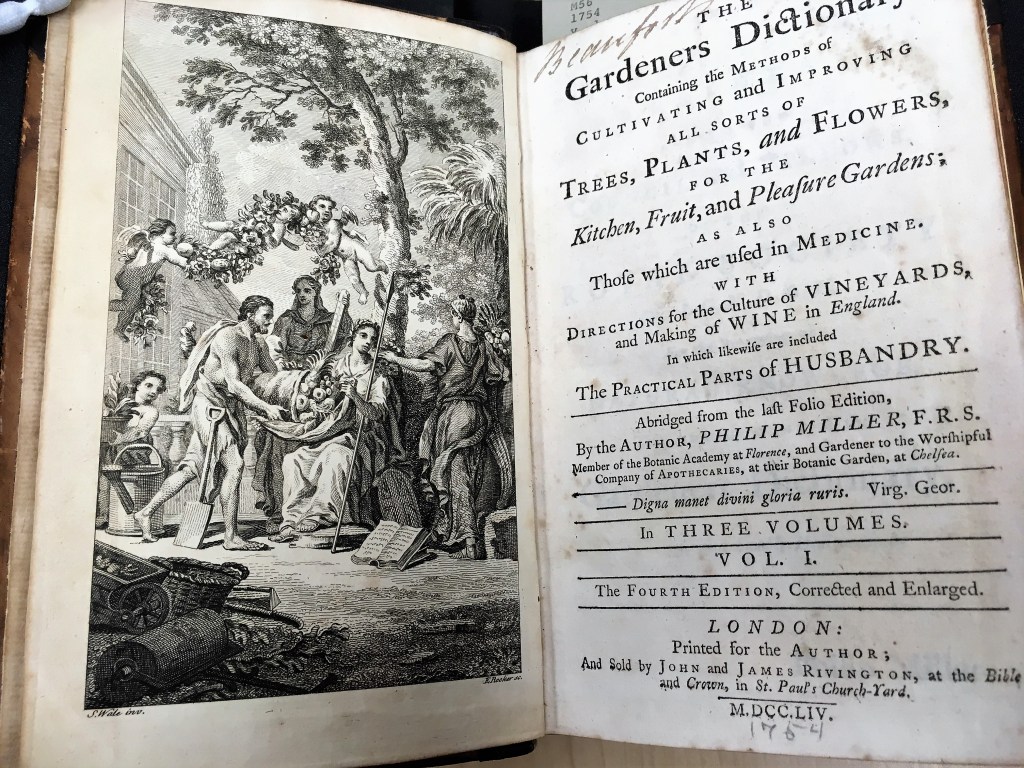

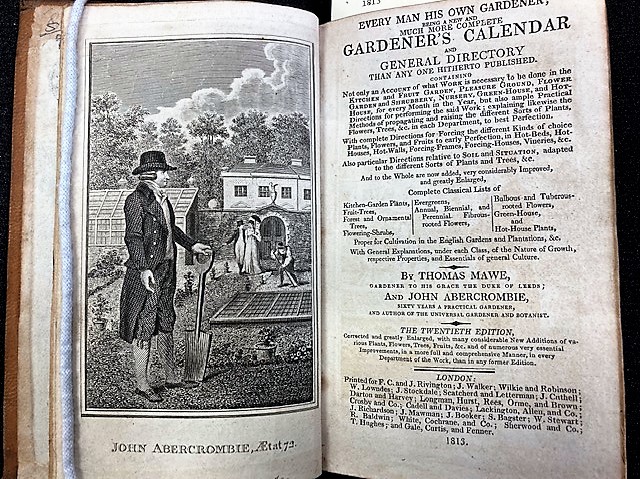

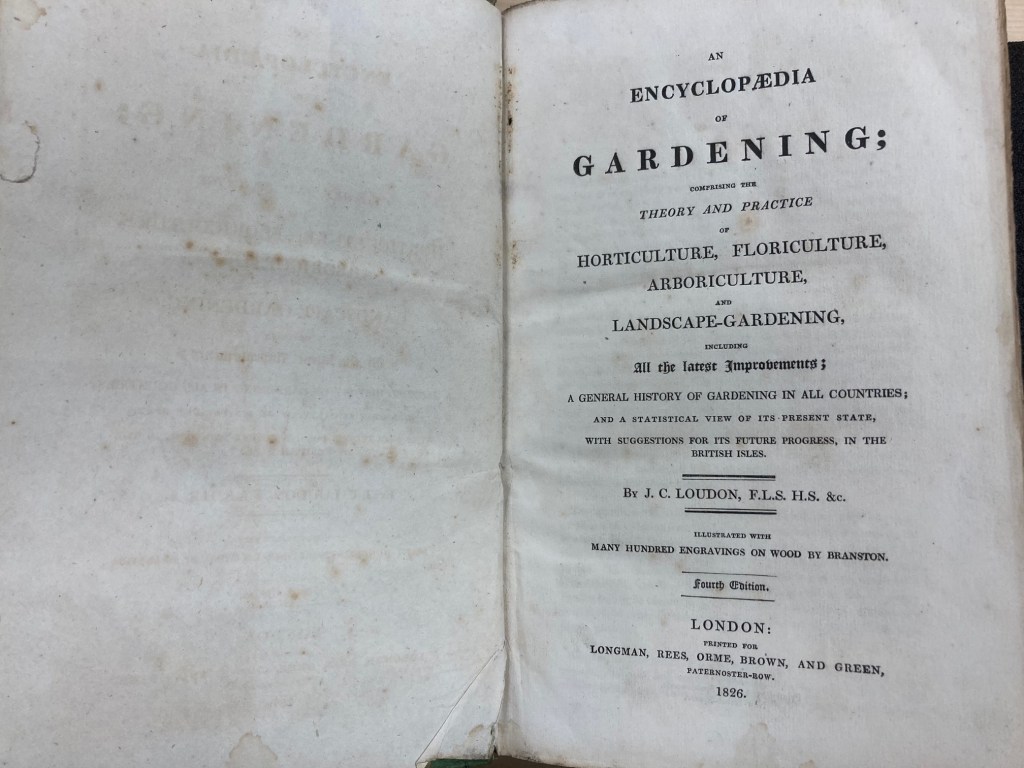

The Estate Library

If Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen Knight, is any indication, owners of estates like Mr. Knightley would have a collection of books about gardening and farming in their library for reference. The 1818 catalogue of the Knight library, which is now searchable at https://www.readingwithausten.com/catalogue.html, lists several gardening and botany books from the eighteenth and early nineteenth century that were popular and went through many editions. Some of the Knight gardening books are organized by type of plant, such as John Evelyn’s Sylva or John Abercrombie’s The Universal Gardener and Botanist (UGB, 1778 first edition)[i]; others are organized by months of the year to describe what work needs to be done in each part of the garden, such as Philip Miller’s Gardeners Kalendar (GK, 1732 first edition); and others focus on methods for propagating and growing plants, such as William Marshall Planting and Ornamental Gardening (1785 first edition) and Abercrombie’s The Propagation and Botanical Arrangements of Plants and Trees (1784 first edition). Other popular gardening books I consulted that are not in the Knight collection are Miller’s Gardeners Dictionary (GD, 1754 edition at MASC), Abercrombie’s Every Man His Own Gardener (EMOG, 1813 edition), which is another gardener’s calendar, and John Loudon’s An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1822 edition online and 1826 edition at WSU MASC; 1835 reprint edition), which summarizes the knowledge of over 100 gardening books from the 1700s and early 1800s. All these books are available online through Google books, and I studied original versions (although usually a different edition) of several of the books at the Washington State University Manuscript, Archives & Special Collections library (see photographs of the MASC books in Illustration Section 1 and the Works Cited list for links to the online versions). These 18th and 19th century books can give us a sense of what was involved in raising fruits and vegetables in Austen’s time.

Illustration Section 1: English Gardening Books from Early 1800s and 1700s

Pictures taken at Washington State University Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections (MASC) by Michele Larrow

Fruits and Vegetables Mentioned in Austen’s Letters and Works[ii]

Before I describe the kitchen garden and orchard, I will review some of the ways fruits and vegetables are mentioned in Austen’s letters and works. Fruits or vegetables, along with other foods, are sometimes used in the story’s context to show the moral failings of a character (see Lane 90-100). Dr. Grant and Mrs. Norris’s argument about the apricot tree, with Dr. Grant’s insult that “these potatoes have as much flavor of a moor park apricot, as the fruit of that tree” (MP I, 6, 94) and Mrs. Norris’s angry defense that the cost to Sir Thomas was “seven shillings, and [it] was charged as a moor park” apricot tree (I, 6, 93), show his selfish gourmand neglect of other people’s feelings and her money-focus and seeking power through Sir Thomas. In Northanger Abbey, when General Tilney’s asks Catherine about Mr. Allen’s “succession-houses” and feels “self-satisfaction” when told Mr. Allen did not care about the garden, along with General Tilney’s complaint-brag that his “pinery had yielded only one hundred in the last year” of very-expensive-to-grow pineapples, are all signs of his greed and relentless focus on social comparison (II, 7, 256, see Wolfson’s note 18; also, Lane 95). While waiting to pick up Lizzy and Jane at an inn, Lydia Bennet’s extravagance and thoughtlessness is shown when she orders “cucumber and sallad” (sallad would mean just lettuce, Lane 65) without having the money to pay for it—cucumbers were quite expensive because they were grown in hot frames, especially for May (PP II, 16, 258, see Spacks note 5). Austen also notes in a letter from Bath that a cucumber will be a “very acceptable present” because it cost 1 shilling (5-6 May 1801). In Sanditon, Mr. Parker’s willingness to leave his ancestral estate and his complaints about the “Eyesore of [the Kitchen Garden’s] formalities; or the yearly nuisance of its decaying vegetation.–Who can endure a Cabbage Bed in October?” in spite of his wife’s obvious “fondness of regret” (MW 380) for the old home show his lack of attention to other’s feelings as an “Enthusiast” seeking to develop Sanditon (371). Of these examples, General Tilney and Dr. Grant are the most morally deficient because they “render the atmosphere in their homes unpleasant” (Lane 93).

Emma is all about eating and growing food and has several characters who reveal themselves through their discussion of food. Mr. Elton’s excessively detailed description of dinner at the Coles to Harriet, with “the Stilton cheese, the north Wiltshire, the butter, the cellery, the beet-root and all the dessert” shows his self-absorption (and lack of romantic interest in Harriet; I, 10, 122; also Lane 91). Mrs. Elton “monopolizing the conversation” (LeFaye 96) while strawberry picking at Donwell shows her desire to dominate and be seen as knowing everything:

‘The best fruit in England . . .–These the finest beds and finest sorts. . . .–Hautboy infinitely superior . . .– Chili preferred—white wood finest flavour of all—price of strawberries in London—abundance about Bristol—Maple Grove—cultivation—beds when to be renewed—gardeners thinking exactly different—no general rule—gardeners never to be put out of their way—delicious fruit—only too rich to be eaten much of—inferior to cherries—currants more refreshing—only objection to gathering strawberries the stooping—glaring sun—tired to death—could bear it no longer—must go and sit in the shade.’”

Emma (II, 6, 406)

Mr. Woodhouse is in his own class in seeking to control what others eat: his “gentle selfishness and being never able to suppose that other people could feel differently from himself” (I, 1, 33) leads to his depriving poor Mrs. Bates of “asparagus and sweetbreads” (as reported by Miss Bates; III, 2, 372), or offering guests “a little bit of tart, a very little bit. Ours are all apple tarts” (I, 3, 54). He wants the Bates’s to cook their apples “three times” (II, 9, 277) and hopes that the ham that was gifted from Hartfield will be “eaten very moderately of, with a boiled turnip and a little carrot or parsnip” (II, 3, 208). Although there is humor in his portrayal, Mr. Woodhouse is a poor host who intellectually is unable to consider other people’s true needs and desires. In these examples from Emma, Austen uses the characters’ interactions around food to show that they are inherently self-centered and contrasts with the true charity of other characters.

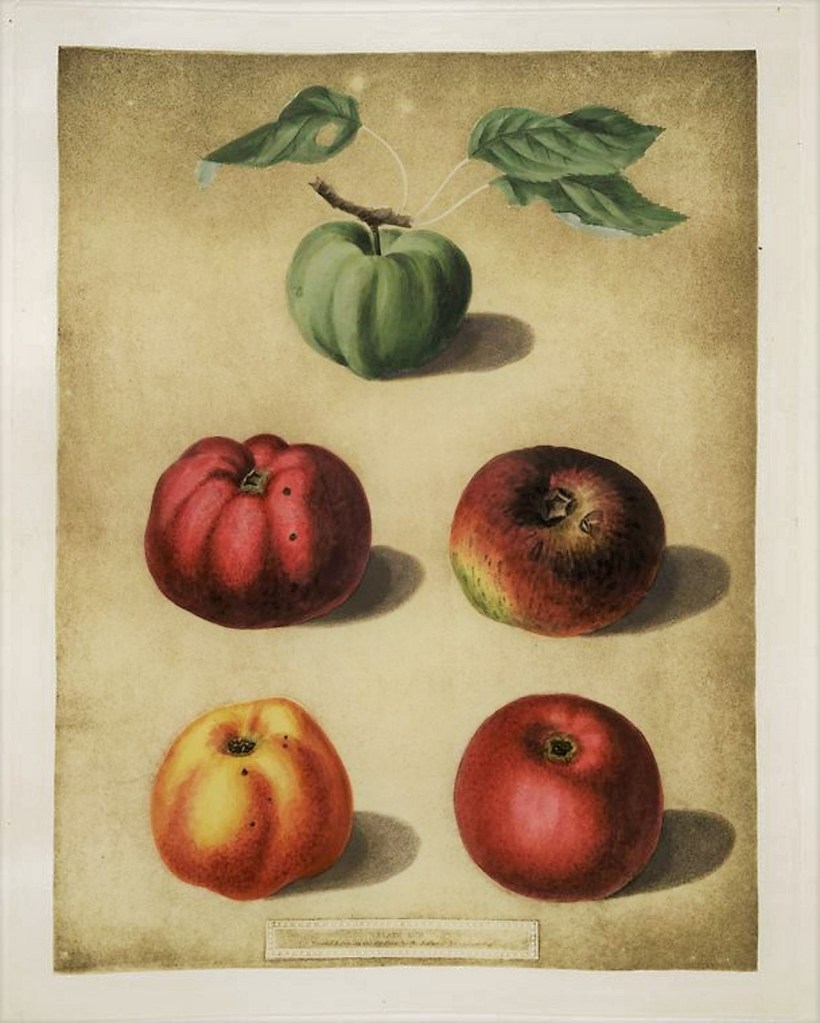

Fruits and vegetables can be special gifts of generosity and hospitality that reflect the giver’s moral worth and bring joy to the recipients. In Emma, Miss Bates learns from William Larkins (Mr. Knightley’s steward) that Mr. Knightley gave them “all the apples of that sort his master had; he had brought them all” (II, 9, 278), so that Mr. Knightley deprives himself of apples for the rest of the spring. Generous Miss Bates invites all her guests (Emma, Harriet, Frank, and Mrs. Weston) to share in the baked apples in that same chapter. In her letters, Austen tells Cassandra with delight about receiving “two hampers of apples” from the Fowle family at Kintbury (24-25 October 1808) and asks her nephew to thank his father (James) “with love” for the “Pickled cucumbers” he sent (16-17 December 1816). Mr. Darcy and Geogianna serve “beautiful pyramids of grapes, nectarines, and peaches” (PP III, 3, 309) to Elizabeth and Mrs. Gardiner, an elegant and welcoming treat for their guests. Sometimes, however, the gift of food fails to comfort, as when young Fanny Price misses home so much that she is not able to eat “two mouthfuls” of the “gooseberry tart” (MP I, 2, 53) without crying and good-natured Mrs. Jennings attempts to soothe Marianne’s broken heart with “dried cherries” (SS II, 8, 237) and “Constantia wine” are rejected, although Elinor drinks the wine instead, reflecting that “its healing powers on a disappointed heart might be as reasonably tried on herself as on her sister” (II, 8, 242; Spacks note 13 says Constantia is a sweet dessert wine made with Muscat grapes).

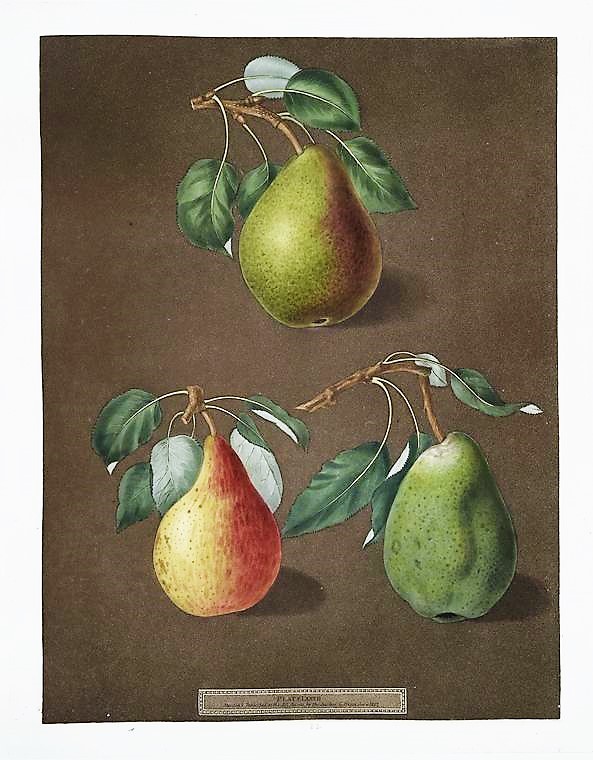

In Austen’s letters, and occasionally in the novels, fruits or vegetables are mentioned in more everyday ways as items grown in the garden or near the house, parts of housekeeping, or food eaten. One of the rare mentions of a pear occurs in Persuasion: “the compact, tight parsonage, enclosed in its own neat garden, with a vine and a pear-tree trained round its casements” (I, 5, 74; “vine” by itself refers to grape vines in that period, see Abercrombie, EMOG 173). In letters to Cassandra, she mentions plans for the garden or the state of the plants: at Steventon “apples, pears, and cherries” are planned (20-21 November 1800) and “Grapes . . . must be gathered as soon as possible” (27-28 October 1798); at Southampton “currant and gooseberry bushes, and . . . raspberries” are planted (8-9 February 1807); while at Chawton, she discusses the number of “Orleans plumbs [and] . . . greengages” (29 May 1811) and “pease,” “strawberries,” “gooseberries,” and “currants” (6 June 1811). Gardens do not always go as planned, producing one of Austen’s funniest lines in a letter: “I will not say that your Mulberry trees are dead, but I am afraid they are not alive.” (31 May 1811). The growth of the garden and its produce is enjoyed by Austen in Chawton, probably especially after living in Bath.

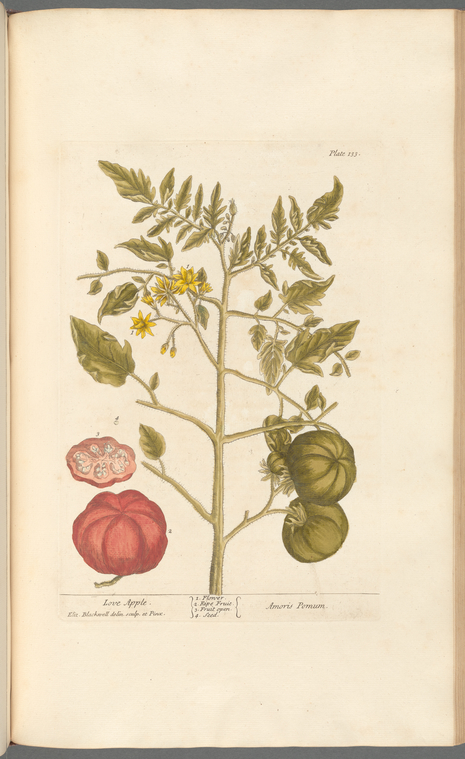

Many of Austen’s letters to Cassandra mention food that was served or eaten. Austen was the deputy housekeeper when Cassandra was away and her mother indisposed so she reports to Cassandra about serving “pease soup” (1-2 December 1798) and “haricot mutton” (17-18 November 1798; Lane shared a 1782 haricot mutton recipe for a stew containing mutton, carrots, turnips, celery, asparagus, cabbage, and cayenne but no beans, 60). Sometimes the housekeeping duties are too much–Austen complains after guests have left Southampton about “the torments of rice pudding and apple dumplings” (7-8 January 1807). While at Godmersham, Austen asks Cassandra if their Chawton garden has the fruit that she is enjoying such as “Tomatas . . . [which] Fanny & I regale on” daily (11-12 October 1813); and when living in Southampton, she writes “I want to hear of your gathering strawberries, we have had them three times here” (20-22 June 1808). Endearingly, when Austen enjoyed “Asparagus & a lobster” at an inn on the way the Bath with her brother Edward’s family, she “wished for” Cassandra to be there too (17 May 1799). While Mrs. Jennings description of eating mulberries from the tree on Colonel Brandon’s estate is seen as somewhat vulgar “Lord! how Charlotte and I did stuff . . .” (SS II, 8, 240) and in the topsy-turvy world of “The Visit”, there is humor in the refined guests feasting on common foods such as “fried Cowheel and Onions,” “Elder wine,” and “Gooseberry Wine” (J 66-67; Sabor notes on 413 that cowheel and onions is “a coarse dish consumed by labourers”; also Lane 80), Austen clearly enjoys everyday foods, especially fruit: “Good apple pies are a considerable part of our domestic happiness” (17-18 October 1815).

The Kitchen Garden

Kitchen Gardens were quite large on estates since they had the land, and it was much cheaper to grow your own food. When the Austen family lived at Steventon, they were largely self-sufficient for food between their kitchen garden and orchards, poultry and dairy, and farm crops (LeFaye 48; Wilson 1). The famous eighteenth century horticulturalist and botanist, Philip Miller (GD Vol. II, “Kitchen Garden”) recommended 1 acre (about 3/4s of a football field) for a small family (which includes servants, see Lane 144) and 3-4 acres (about 3 football fields; see Video 2 of Hillsborough Castle for a 4-acre walled garden) for a large family, built on one side of the house, near the stables (for dung) and near water. Abercrombie writes that a kitchen garden of about an acre can be cared for by one gardener and larger gardens would need more help (UGB “Kitchen Garden”). The kitchen garden would have square or rectangular beds divided by walkways. Miller suggested surrounding the garden with a 12-foot wall for training fruit trees and to keep out animals that would eat the food. The area within the wall would have a wide dirt border (about 12 feet) to support the wall-trained trees. There was also space for glass-topped frames for growing melons and cucumbers that need protection from the cold. Nursery beds are sheltered beds where seedlings and cuttings could grow, often spaced more closely together than how they will grow when transplanted in their permanent spot. Loudon (1826 edition) gives an example of a kitchen garden design and diagrams the parts, as seen in illustrations 4.1 and 4.2 below. In Video 1 of Walmer Castle and Video 2 of Hillsborough Castle, there are several aerial shots over the kitchen gardens so you can see the scope of them (see the end of the blog text for the video links).

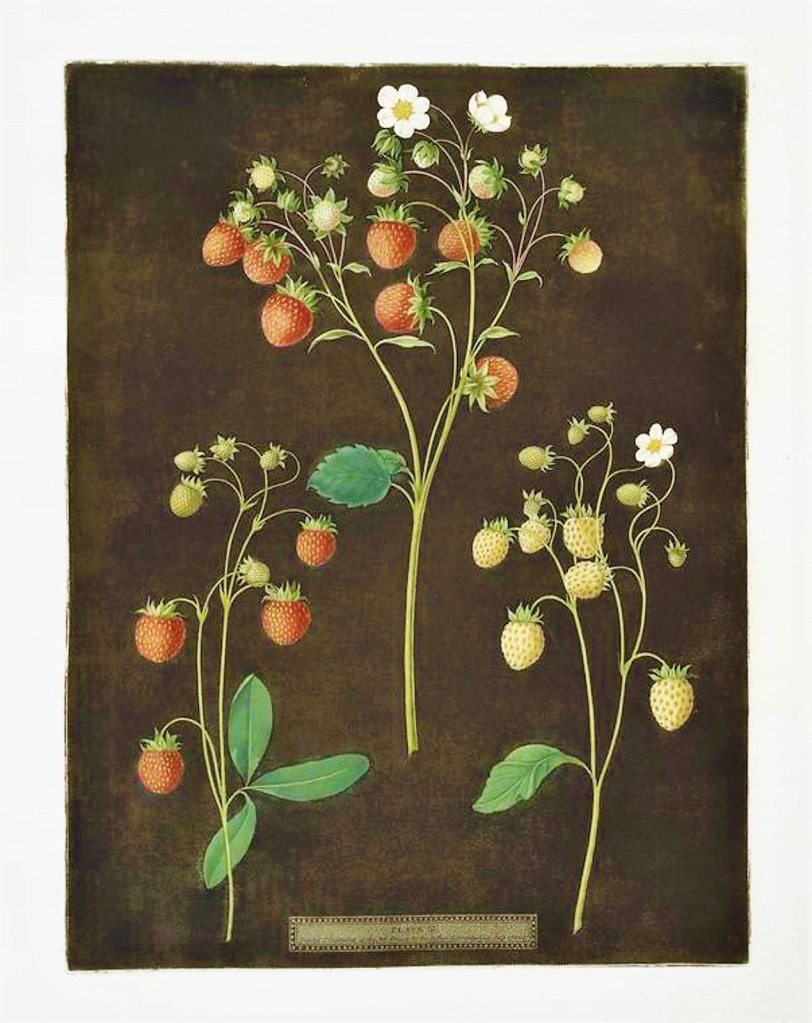

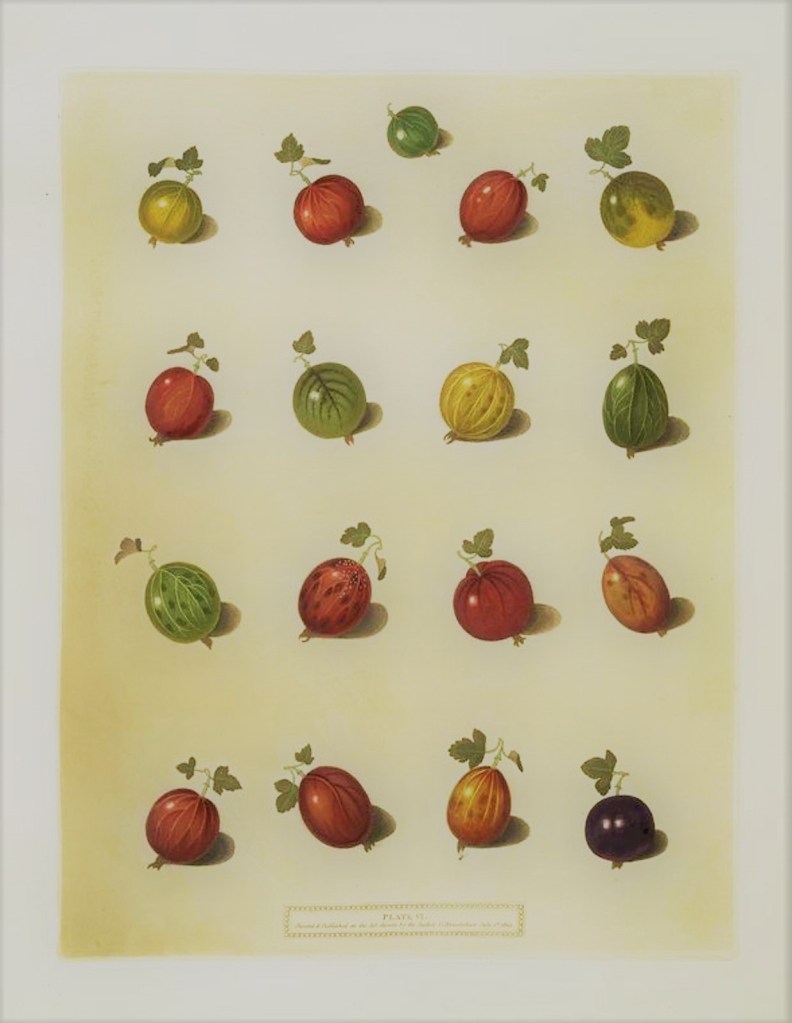

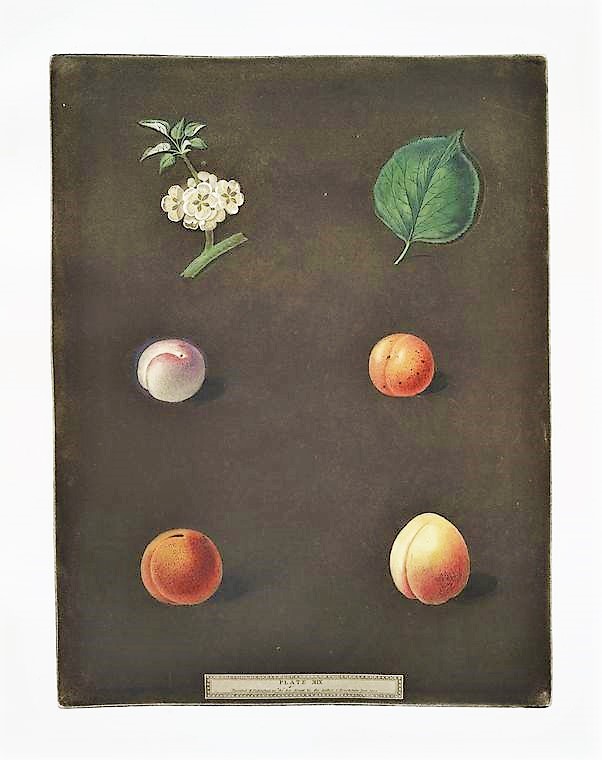

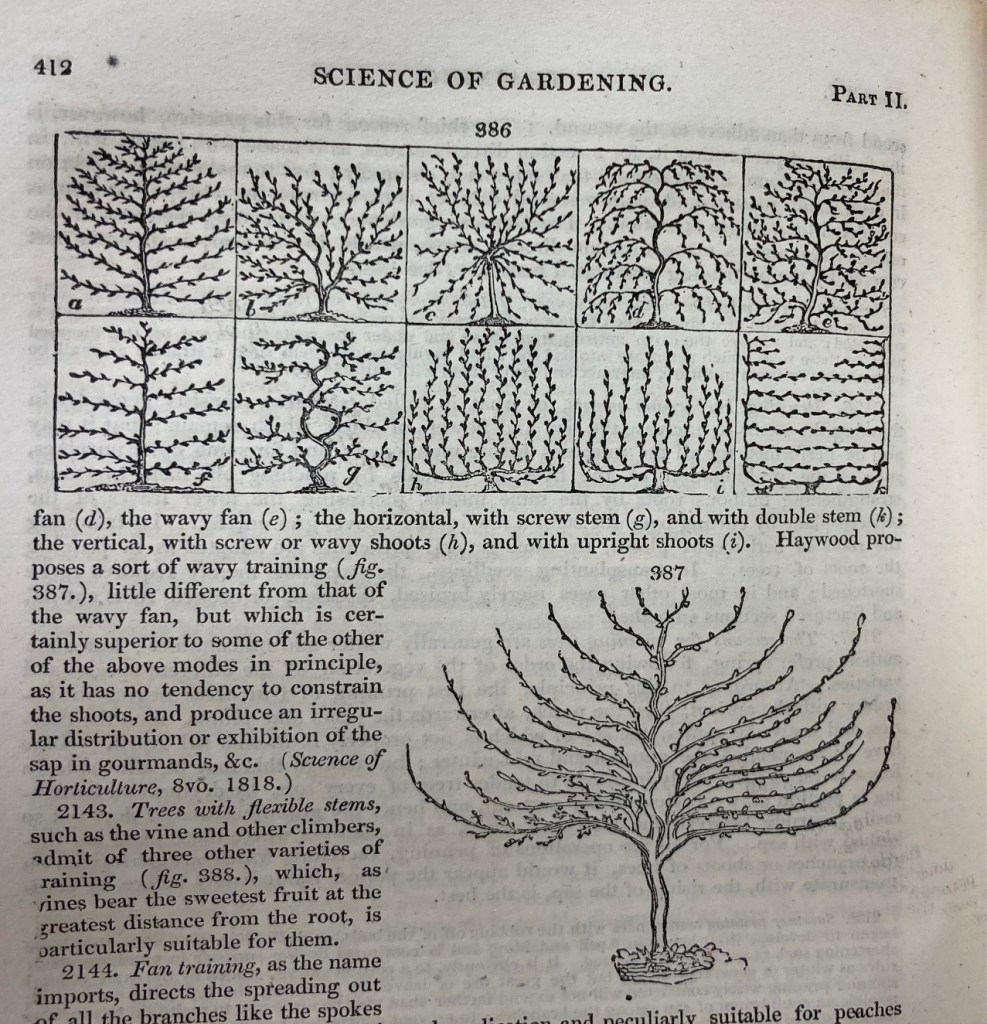

Colonel Brandon’s estate Delaford is described by Mrs. Jennings as “quite shut in with great garden walls that are covered with the best fruit trees in the country” (SS II, 8, 240) and Donwell Abbey’s kitchen garden was probably very similar. Fruit trees that are trained against the south-facing garden wall have a more protected and warmer growing environment for earlier blooming or more cold-sensitive fruit. Trees grown on the north-facing walls would be somewhat later blooming and bear fruit later, to prolong the fruit’s season (Miller, GD Vol. 2“Kitchen Garden”). Almost every fruit tree mentioned in Austen’s works or letters could be trained against garden walls (at least in the southern English counties) include apples, pears, plums, cherries, apricot, peaches, nectarines, and grapes (the last three fruits are in Pride and Prejudice, where they would have been grown in forcing houses since Derbyshire is so far north—see my prior blog https://jasnaewanid.org/2022/07/30/mr-darcys-fruit/ ). Fruit trees such as apples and pears trained onto garden walls or espalier (trained on fences as Robert Martin’s apple trees are in Emma II, 5, 224)[iii] would be pruned into a single flat layer of branches growing horizontally from the trunk of the tree, about 4-6 inches apart and allowed to grow to full length (Abercrombie, EMOG; Miller, GD Vol. 3 “Training”) and stone fruits would be trained into a fan pattern (Loudon 1835 668-671; see below for illustration 4.3 for pruning shears, 4.6 for an iron espalier rail, and 4.7 for training patterns from the 1826 edition). Figs are also wall-trained although they can grow as standards (Loudon, 1835 959). Gooseberries and currants grow on bushes, often trained as “standards” with a single stem topped by several branches with fruit and might line walkways in the kitchen garden about 6-10 feet apart (Loudon, 1835 743; Miller, GD Vol. II “Kitchen Garden”). Raspberries, a native of Britain, usually are grown as shrubs best planted in a shadier spot of the garden, although they are also used to line walkways (Loudon 1835 935-937). Mulberries were sometimes trained against kitchen garden walls but more often would be a stand-alone tree, as it appears to have been at Delaford since Mrs. Jennings described it as “such a mulberry tree in one corner!” (SS II, 8, 240), either placed in the kitchen garden (especially in the 1700s), in the pleasure grounds, or in the orchard. Mulberries take several years to produce fruit and can live to an old age still producing (Loudon, 1835 927). Strawberries would be grown in beds in the kitchen garden, planted in rows a foot apart with plants spaced from 8-24 inches apart depending on the size of the strawberry variety (Miller, GD Vol. 1, “Fragaria”). George Brookshaw’s Pomona Britannica (1812) has beautiful illustrations of many fruits, showing the many varieties especially of strawberries, gooseberries, cherries, apricots, plums, peaches, nectarines, grapes, pears, and apples, as well as the currants and raspberries, which just have two or three varieties (see Section 2 for a selection of the plates).

Illustration Section 2: Fruits from George Brookshaw’s Pomona Britannica

Illustration Credits list the exact fruit pictured and give a link for the digital copy

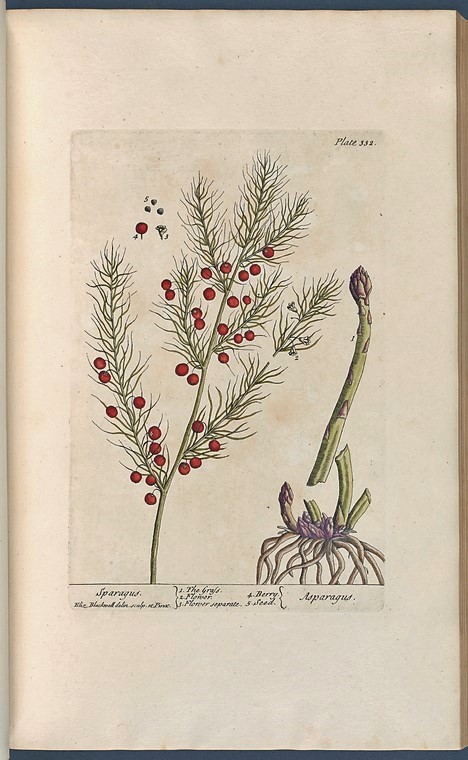

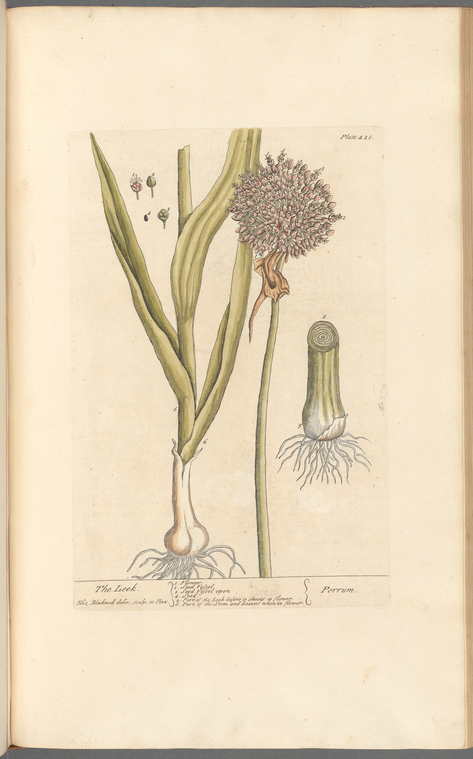

There would also be a large variety of vegetables grown in the kitchen garden. Austen’s family grew peas, tomatoes, and potatoes at Steventon and Chawton (Wilson 4, 46 and LeFaye 21, 248). Other vegetables mentioned in Austen’s works and letters that would be in the kitchen garden include celery, cucumber, beets, cabbage, carrots, turnips, onion, parsnip, and asparagus. Also grown in the kitchen gardens at the time, though not mentioned by Austen, are broccoli, cauliflower, artichokes, leeks, radish, beans, hot peppers, and many herbs (see Miller, GD and Abercrombie, EMOG). Most of the vegetables would be grown from seed and planted annually; Miller recommends changing where the plants are grown in the garden each year (GD Vol II “Kitchen Garden”). Loudon discusses the rotation of vegetable and some fruit crops in more depth: recommending annual rotation of the “brassica tribe [cabbage family], the leguminous family, the tuberous and carrot-rooted kinds, the bulbous or onion kinds; and the lighter crops, as salads and herbs” (Loudon, 1835 749). Strawberry beds should be renewed every 4-5 years. Artichokes, asparagus, currants, gooseberries, and raspberries should be renewed every 7-8 years (Loudon, 1835 748-749). To maximize the length of time that specific vegetables were available fresh, the vegetables grown from seed would be sown at regular intervals many times through the growing season, such as lettuce, celery, peas, beans, carrots, radishes, etc. (Abercrombie, EMOG) starting as early as January and lasting through December (Loudon, 1835 1245-1260). Asparagus is started as a seed, but the roots do not produce stalks until after 3 years; the stalks come up annually after that and are best when harvested in May and June (Abercrombie, UGB “Asparagus”). Vegetables such as celery, asparagus, and endive would be grown using a process called “earthing” where the stalks are covered with earth to keep the vegetable “white, tender, and palatable” (UGB “Apium”). Other vegetables like potatoes would be planted in March or April from chunks of potato with one or two eyes and then harvested in the fall (Abercrombie, EMOG 37, 159). Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal, originally published in 1737-39, has illustrations of several vegetables grown in the kitchen garden (see Illustration Section 3).

Illustration Section 3: Vegetables from from Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal

Illustration Credits list the vegetable pictured and give a link for the digital copy

Orchard

Mr. Wentworth, Mrs. Croft and Captain Wentworth’s clergyman brother, is described thus by Sir Walter’s lawyer, Mr. Shepard: “came to consult me once, I remember, about a trespass of one of his neighbours; farmer’s man breaking into his orchard—wall torn down—apple stolen—caught in the fact; and afterwards, contrary to my judgment, submitted to an amicable compromise.”

Persuasion I, 3, 59

Since orchards have large trees, they can produce a great deal of fruit that is valuable for both home baking and dessert eating and for sale (and potentially pilfered, as Mr. Wentworth found in Persuasion). We know in Emma that Mr. Knightley sells most of his apples when he tells Miss Bates, as reported by her, that “William Larkins let me keep a larger quantity than usual this year” telling her a white lie to convince her to accept his gift of apples (II, 9, 278). At the strawberry picking party, the “orchard in blossom” that Emma sees looking down to Abbey-Mill Farm, Robert Martin’s prosperous farm that he rents from Mr. Knightley, is seen as one of Austen’s few mistakes in facts, since orchards usually bloom in May (III, 6, 409). Austen enjoyed orchards for both their beauty and utility; in a letter to Cassandra from Chawton, she tells her “You cannot imagine, it is not in Human Nature to imagine what a nice walk we have round the Orchard” (31 May 1811).

Philip Miller recommended that orchards be situated on gently rising ground (not a hill) open to the southeast so that trees are exposed to the right amount of “the Sun and Air” (GD Vol. II, “Orchard”). He also prefers that the trees be defended from winds from the west, north, and east and that a screen of timber trees be planted around the orchard if it is not naturally protected by hills. Trees should be planted “fourscore [80] feet asunder not in regular rows.” Wheat and other crops can be planted between the trees in order to plow and till the soil, which makes the trees “more vigorous and healthy”. Miller focuses on stone fruit, apples, pears, and cherries in the orchard. Trees should be planted in the spot they will stay in when young and been previously raised in similar soil to the orchard in the nursery bed. Once the trees are established, they should only be pruned to take off dead branches.

In The Gardener’s Encyclopaedia, John Loudon summarizes several different gardeners’ writings on orchards, saying that they can be between 1 and 20 acres, depending on land and demand for the fruit (1835 744-746). Alternatively, large fruit trees can be distributed among the ornamental plantings on an estate. Hardy fruits such as apples, pears, cherries, plums, medlar, mulberry, quince, walnut, chestnut, filbert, berberry make for a complete orchard. If fruit is grown for sale, “apples are first in utility” and pears, cherries, and plums “are acceptable” for cooking with (1835 744). Orchards are best planted in the autumn and Loudon recommends that trees be spaced about 30-40 feet apart.

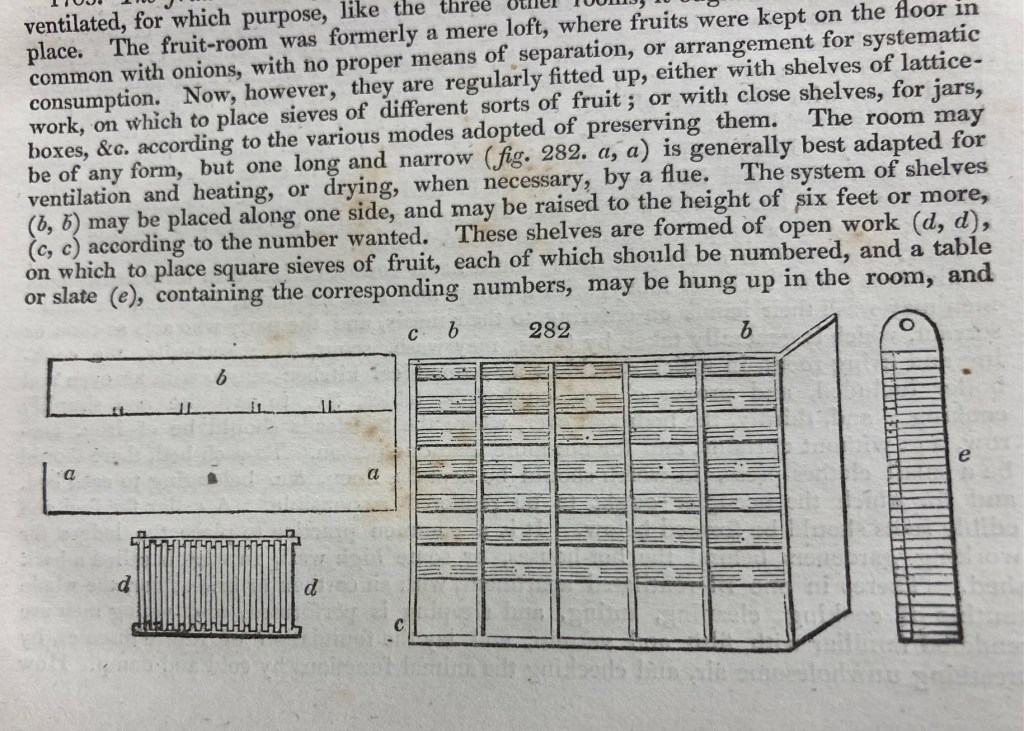

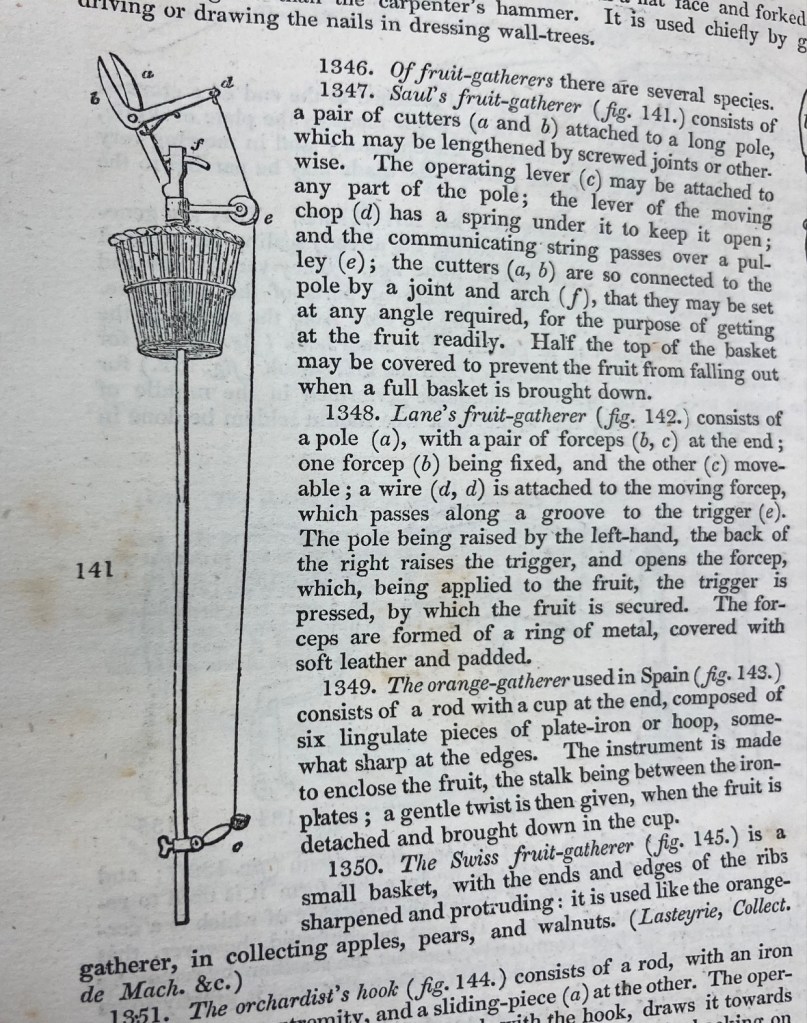

We wrote in a previous blog https://jasnaewanid.org/2022/06/04/pomona-britannica-and-emma/ that apples and pears had hundreds of varieties in the 1700 and 1800s, some varieties would ripen in mid-summer and others in late fall/early winter and then would finish ripening off the tree in storage, to ensure almost a year-round supply of the fruit (especially of apples). Miss Bates says of Mr. Knightley’s apples “there never was such a keeping apple anywhere as one of his trees—I believe there is two of them. My mother says the orchard was always famous in her younger days” (E II, 9, 278). Orchard tree fruit should be picked by hand (using ladders or using a fruit gatherer, like illustration 4.4) to keep it as unblemished as possible—windfalls and those shaken down are liable to bruise and spoil easily. According to Miller (GD Vol II “Malus”), late ripening apples should be left on the tree as long as possible (until frost) and then picked in dry weather, sweated in piles for 3-4 weeks, wiped dry, and stored in large oil jars. Jane Austen stored her “two hamper of apples” from Kintbury on the floor of the “garret” when living in Southampton to keep them cold (24-25 October 1808). Larger estates would have fruit rooms with regulated temperature where fruit was kept on shelves of open lattice for air circulation, which also allows easy access to take out the fruit for consumption throughout the winter (Loudon, 1835 760 and illustration 4.5). Apples and pears for keeping would be stored in jars or barrels in the temperature controlled (32℉ to 40℉) fruit cellar and not opened until needed in the spring, lasting into May or June (Loudon, 1835 759-761). With careful management, apples and pears could be eaten year-round.

Illustration Section 4: Illustrations from An Encyclopaedia of Gardening by John C. Loudon, 1826 edition

Pictures taken at Washington State University Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections (MASC) by Michele Larrow. The book was propped to preserve the spine so the pictures are not flat. For 4.2 Diagram of a Kitchen Garden a=slips, b=walls c=walks, d=quarters (beds), e, h, k=rooms, f=compost & hot-beds, g=gardener’s house, m=fountain/water, p=open railing, q=irregular borders

June in the Kitchen Garden and Orchard

In the 1700 and 1800s, there were several calendars for gardeners that helped them to keep track of what needed to happen when in the gardens. Philip Miller’s Gardeners Kalendar was owned by Austen’s brother Edward. John Abercrombie’s Every Man his Own Gardener gives even more details about the work that needs doing than Miller’s Kalendar. Miller offers us a list of the fruits that would be ripe in June, such as strawberries, currants, gooseberries, cherries (trained on walls) and in forcing houses peaches, nectarines, and grapes. He also notes that “carefully preserved” keeping apples such as Golden Russet and Stone Pippin, would still be good (GK 187). The vegetables available in the kitchen garden would be cauliflower, cabbage, young carrots, beans, peas, artichokes, asparagus, turnips, cucumbers, salad herbs, some celery, and melons (GK 183). Because of the protection of the kitchen garden walls, much produce would be available as early as June.

In the June Kitchen Garden, Abercrombie recommends constant weeding and watering when plants are dry. Beets, onions, carrots, and parsnips are to be thinned. Lettuce, peas, turnips, and cabbage can be first planted or sown again for use later in the summer (lettuce and peas) and in the fall and winter (turnips and cabbage). Celery would be planted at different times for a continuous supply over the summer and earthing (packing dirt around the base) takes place in June. Asparagus stalks should not be cut after June 24th to keep the roots strong. Cucumbers would be grown in frames and were sown in January and February for summer consumption. On June days, the frames would be opened to allow air and they would be shaded from the sun during the hottest parts of the day (EMOG 1787 283-300).

For the fruits in the Kitchen Garden, in May and June wall-fruits such as apricots, peaches, nectarines, apples, pears, cherries, and plums should be thinned, taking off many of the fruits and only leaving those that are the best shape and the biggest (and only as many as the size of the branch can support). The young fruit that is taken off can be used for tarts. Additionally, the fruit trees need to be pruned of shoots that are not productive to fruit either this year or next. Grapes vines should be pruned in May and June of all shoots that are weak or non-productive. The strawberry beds produce runners in June that can be planted for next year (or even for the winter if planted in frames; Abercrombie, EMOG 1787 252-253, 301-307).

Conclusion

An incredible amount of labor went into producing food in Jane Austen’s time. Mr. Knightley would undoubtedly have at least one gardener to work in his garden, separate from William Larkins, who functions as his steward, managing the estate, including going over the books with him. The gardens involve numerous tasks in every month of the year, whether it is pruning hardy fruit trees in January, planting seeds and bulbs in March, destroying insects in May, sowing autumn vegetables in July, planting cuttings of shrub-fruits in September, or storing late fruit in November (see Loudon, 1835 1243-1260 for a short Kalendarial Index). The goal in the kitchen gardens was to have fresh fruit and vegetables as early as possible and lasting as long as possible through the year.

In our next blog, I will cover the pleasure grounds, including flower beds, shrubbery, ornamental woods, as well as the growth of trees for sale as timber. I will also discuss the use of greenhouses and hot-houses for growing cold sensitive plants in that blog.

Videos

These videos all show examples of walled kitchen gardens on large estates in the British Isles. Thanks to region member Sara Thompson for video suggestions.

Video 1: https://youtu.be/WE2kkFMTFIY Walmer Castle Kitchen Garden (about 4 minutes)Spring in the walled kitchen garden with espalier trees, beans, asparagus, strawberries, cold frames.

Video 2: https://youtu.be/aLu_P69ZkuI Hillsborough Castle Walled Garden Autumn Harvest (about 4 minutes; Northern Ireland British Royal Palace) 4-Acre Walled Garden with espalier pear trees; shows lots of vegetables also.

Video 3: https://youtu.be/vop2ZpK7fbY Audley End House Kitchen Garden in Spring (about 14 minutes) Walled kitchen garden that includes espalier apples in bloom, potting tomatoes, a peach house and a vinery.

Video 4: https://youtu.be/ssAoqhrVT28 Audley End House Kitchen Garden: Picking Apples in Fall (about 11 minutes) Picking apples growing in the walled garden on espalier wires and walls. Although this video is described as gardening practices in the Victorian era, the advice about how to pick the apples is the same as what was written in the 1700s and early 1800s.

NOTES

[i] The title page of several of Abercrombie’s works lists Thomas Mawe as the first author, but in fact he did not contribute to the works (see introduction to the EMOG book and the title listing of the 11th edition in WORKS CITED), so I am listing Abercrombie as the sole author for EMOB and UGB.

[ii] The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press editions of the six novels were used for reference (NA=Northanger Abbey, SS=Sense and Sensibility, PP=Pride and Prejudice, MP=Mansfield Park, E=Emma, and P=Persuasion). These editions have excellent annotations often with illustrations about gardening, food, and landscaping, as well as other topics. For ease of comparison to other editions, I have included the Volume and Chapter of each quotation, as well as the page number in the edition used. See the Works Cited section for the specific editions used of the Minor Works (MW) and Juvenilia (J). For Jane Austen’s Letters (L), I used the Diedre Le Faye 3rd Edition, 1995 and am indebted to the wonderful searchable index of subjects for that edition created by Del Cain in 2002 and available at: https://www.mollands.net/etexts/ltrindex/index.html.

[iii] The term “espalier” was used in the 1700s and early 1800s only to refer to fruit trees that are trained against rails or fences into a flat pattern. Fruit grown against walls would be called “wall trees”, see for example Loudon, 1835, 1252. In current usage, espalier refers to 1. a tree that is trained to grow into a flat pattern against a wall or other supports or 2. the supports itself (as a noun) and 3. the process of training the tree to grow in a flat pattern (as a verb; see dictionary.com).

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

Illustration Set 2: Fruits

Most of the fruit illustrations are from George Brookshaw’s Pomona Britannica (1812). Digital copies were color-enhanced to correspond to the prints available in George Brookshaw Pomona Britannica: The Complete Plates, Koln, Germany: Taschen, 2002.

2.1 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Wood strawberry – The new early prolific strawberry – White Alpine.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8858-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.2 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Red and the White Antwerp Raspberries.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8864-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.3 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Black currant – Dutch red and white currants.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-886a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.4 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Sixteen varieties of Gooseberry.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8876-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.5 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “May-Duke, the White and Black-heart Cherries.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-887f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.6 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Drap d’Or, or Cloth of Gold, White gage, Blue gage and Green gage plums.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-889c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.7 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Royal Dauphin, Wine sour, Prune, Myrabolan and Carnation plums.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. [Note: These are apricots and are labeled incorrectly as “plums”] https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-88b6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.8 Hooker, William. Pomona Londinensis: Containing Colored Engravings of the Most Esteemed Fruits Cultivated in the British Gardens : with a Descriptive Account of Each Variety. United Kingdom, W. Hooker, 1818. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pomona_Londinensis/wDVKAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1, plate 9

2.9 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Red nutmeg, Hemskirk, Early Ann and French Vanguard Peaches.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-88c6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.10 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Vermash, Violette Hative, Red Roman, North scarlet, Ell rouge and the Peterborough nectarines.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-88e9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.11 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Black muscadine (grapes).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8931-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.12 Blackwell, Elizabeth. A Curious Herbal… Engraved… by Elizabeth Blackwell…. United Kingdom, John Nourse, 1739/1751. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “The mulberry tree” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/19cfebd0-fcde-0136-5175-0d7952ce55cb

2.13 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Pears (Brown beurree, Golden beurree and the COlmar varities).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-899c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.14 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Apples (White Colville, Red Colville, Norfolk Beefin, Norfolk paradise, Norfolk storing varities).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8b7a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

2.15 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Apples (Phoenix and the Norroway’s beauty varities).” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8b6a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Illustration Set 3: Vegetables

Most of the vegetable illustrations are from A Curious Herbal, illustrated by Elizabeth Blackwell. This edition was published in 1751, it was originally published in 1737-39.

3.1 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Artichoke” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1739. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7cc98c60-6da5-0136-f4fe-0d6ad4614061

3.2 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Sparagus” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1739. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/13d191c0-6da7-0136-469d-0f917af7af15

3.3 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “The bean” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/f1e370b0-fcdd-0136-1a19-00dcd1e3eb67

3.4 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Red beet” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5f9e3470-fce0-0136-0588-339a3bceb83b

3.5 Deutschlands Flora in Abbildungen Echte Möhre, Daucus carota Artist Jacob Strum https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daucus_carota_Sturm12033.jpg

3.6 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Garden cucumber” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ec3f0ba0-fcdd-0136-e197-0c7e27bce827

3.7 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “The leek” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1739. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/131de310-6da6-0136-72b5-085faccb9d2c

3.8 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Lettice” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/0b833750-fcde-0136-14a7-0117869a6c24

3.9 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Peas” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/09b7acf0-fcde-0136-b64d-0819a9ad2c1f

3.10 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Guinea pepper” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1afd19f0-fcde-0136-2309-4715cdcab7dc

3.11 George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Garden radish” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/091f6030-fcde-0136-aa1c-0574f4b1e236

3.12 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Love apple” [Tomato] The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1c73fe80-fcde-0136-5330-3d2b7c157681

3.13 Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Turnep” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1751. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5abe7a40-fce0-0136-664c-04524d9e1f4c

WORKS CITED

Abercrombie, John Every Man His Own Gardener Being a New, and Much More Complete Gardener’s Kalendar … By Thomas Mawe … John Abercrombie … and Other Gardeners [or Rather, by John Abercrombie Alone]. The Eleventh Edition, Corrected and Greatly Enlarged London: various publishers, 1787. https://books.google.com/books?id=R8NgAAAAcAAJ; 1813 edition used at WSU MASC.

Abercrombie, John. (Also lists Mawe, T. as an author but he did not contribute). The Universal Gardener and Botanist London: G. Robinson, Pub., 1778. This is the same edition that Edward Austen Knight owned. https://books.google.com/books?id=eMtCAQAAMAAJ

Austen, Jane. Emma. Ed. Bharat Tandon. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2012.

____. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Fay. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

____. Juvenilia. Ed. Peter Sabor. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

____. Mansfield Park. Ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2016.

____. Minor Works. Ed. R. W. Chapman, 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1953/1967.

____. Northanger Abbey. Ed. Susan J. Wolfson. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2014.

____. Persuasion. Ed. Robert Morris. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2011.

____. Pride and Prejudice. Ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2010.

____. Sense and Sensibility. Ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, 2013.

Brookshaw, George Pomona Britannica: The Complete Plates, Koln, Germany: Taschen, 2002.

Lane, Maggie. Jane Austen and food. London: Hambledon Press, 1995.

Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen’s Country Life. London: Frances Lincoln, 2014.

Loudon, John Claudius. An Encyclopaedia of Gardening, comprehending the theory and practice of horticulture, floriculture, arboriculture and landscape gardening. London: Longman, 1822. https://books.google.com/books?id=6vqUeGAey64C (1826 edition available at WSU MASC; a 1835 second edition was also consulted in print from the 1982 reprint by Garland Publishing in the English Landscape Garden series, 2 volumes).

Miller, Philip. The Gardeners Dictionary, 1754 edition (at WSU MASC) London. Vol 1: https://books.google.com/books?id=ko9cAAAAcAAJ Vol 2: https://books.google.com/books?id=C1wZAAAAYAAJ Vol 3: https://books.google.com/books?id=NuRi8m3xvykC

Miller, Philip. Gardeners Kalendar, Fourth Ed. London: C. Rivington, Pub,1737. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSFWAAAAYAAJ 1732, first edition in Knight collection and Fourteenth Edition, 1765 available at WSU MASC.

Wilson, Kim. In the Garden with Jane Austen. London: Frances Lincoln, 2008.