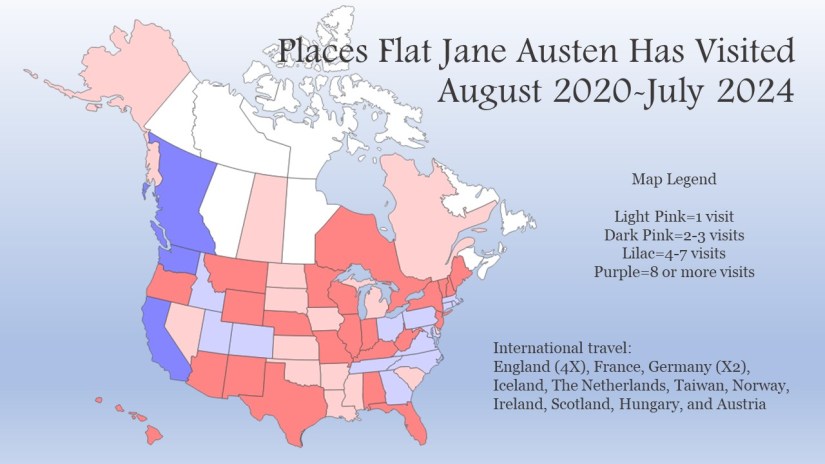

Michele Larrow, Regional Co-Coordinator

“The gardens or pleasure grounds near a house may be considered as so many different apartments belonging to its state, its comfort, and its pleasure.” Humphry Repton, Fragments 165

Jane Austen would likely agree with Regency-era landscape gardener Humphry Repton that the gardens or pleasure grounds around the house are a source of comfort and pleasure; her heroines experience the beauty of nature and freedom to roam in the pleasure grounds near a house. During the Regency era, the pleasure grounds were part of the estate, typically near the house, that contained flower gardens and shrubberies, as well as ornamental woods with paths. The kitchen gardens, orchards, and greenhouses or hot houses usually were in a different location than the pleasure grounds, and also near the house (see our two previous blogs: The Donwell Abbey Kitchen Garden and Orchard and Mr. Darcy’s Fruit for further information). The park was a separate part of larger estates used for hunting and riding, which was often left in a more natural state. During the Georgian and Regency periods, shrubberies were important garden elements that were found even in smaller houses and cottages, such as Austen’s last home at Chawton Cottage. Shrubberies are mentioned in the six novels, in a couple of stories in the Juvenilia, and in Lady Susan (29 times for “shrubbery” and 9 times for “shrubberies”). This blog uses ten quotations from Austen’s works and letters to discuss five aspects of shrubberies and other elements of the Regency pleasure grounds.

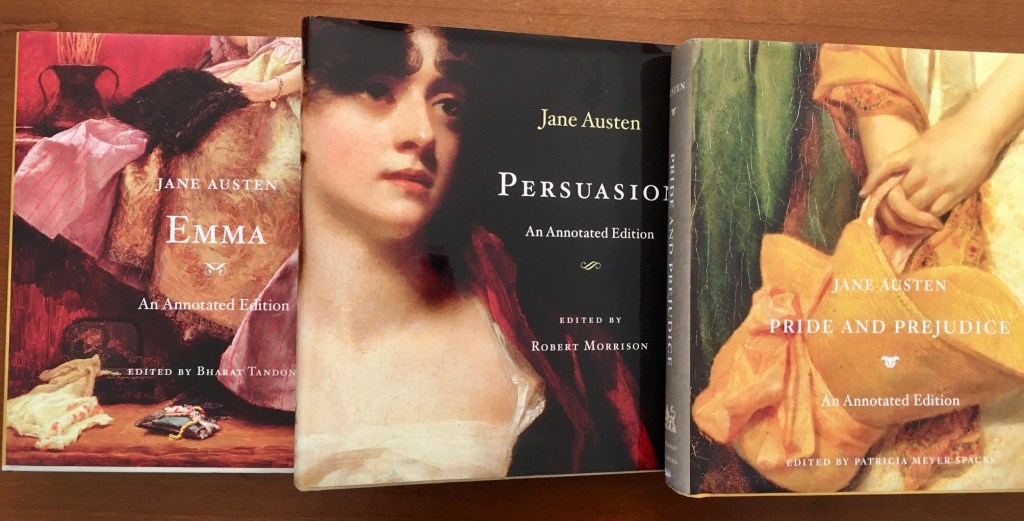

A Note about the Austen Texts: The Cambridge Edition of the six novels is used for almost all references, except for Chapman’s Minor Works (MW) for Lady Susan and when Chapman’s chronology is consulted and then the Chapman edition Appendices are cited. As is standard, NA=Northanger Abbey, SS=Sense and Sensibility, PP=Pride and Prejudice, MP=Mansfield Park, E=Emma, and P=Persuasion. The full citation for each novel is listed in the Works Cited at the end of the blog.

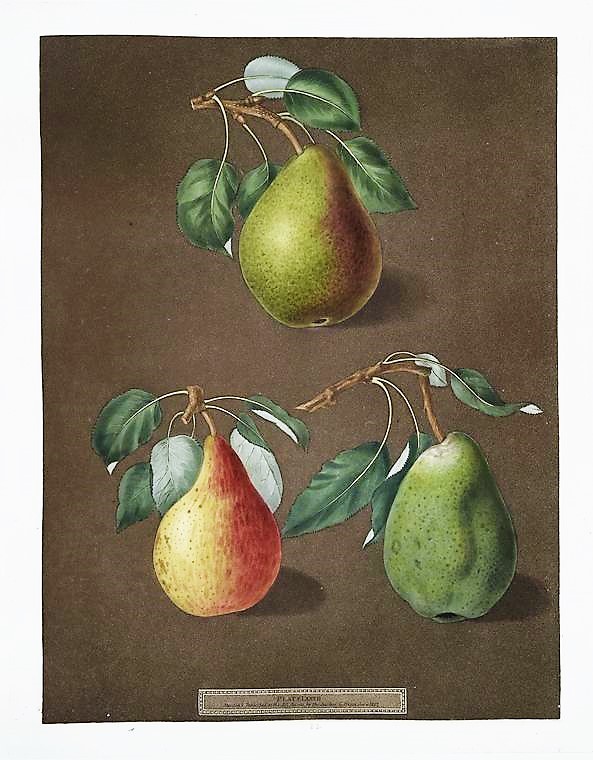

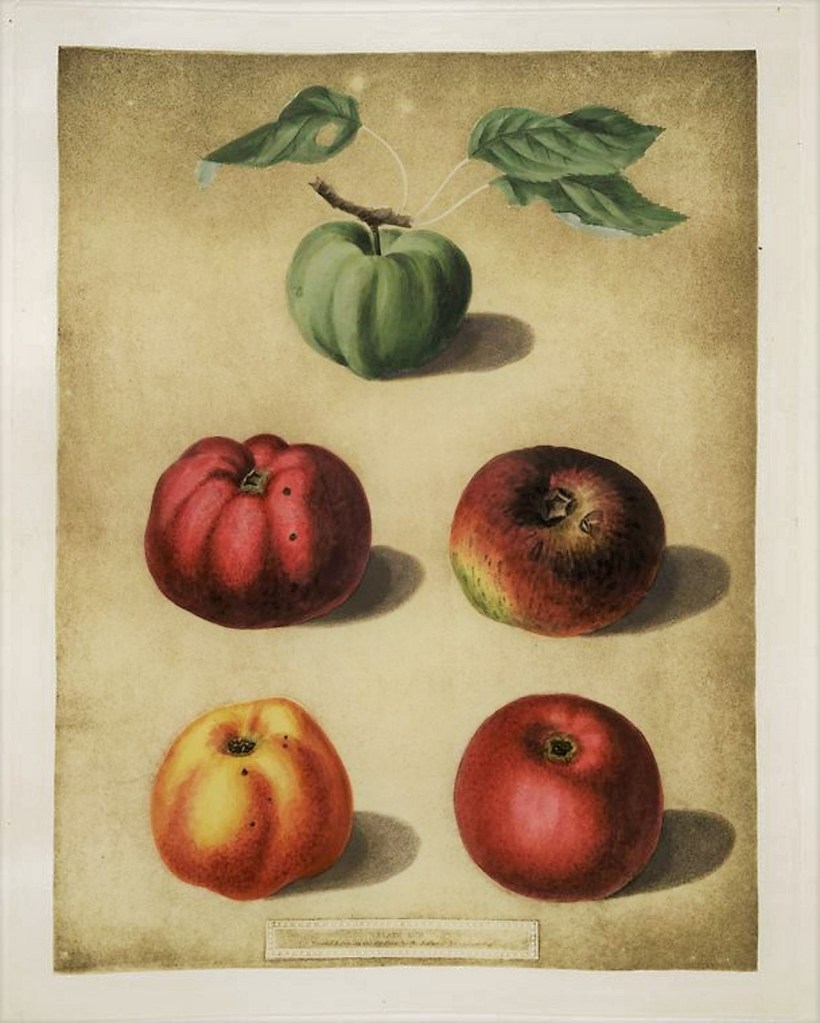

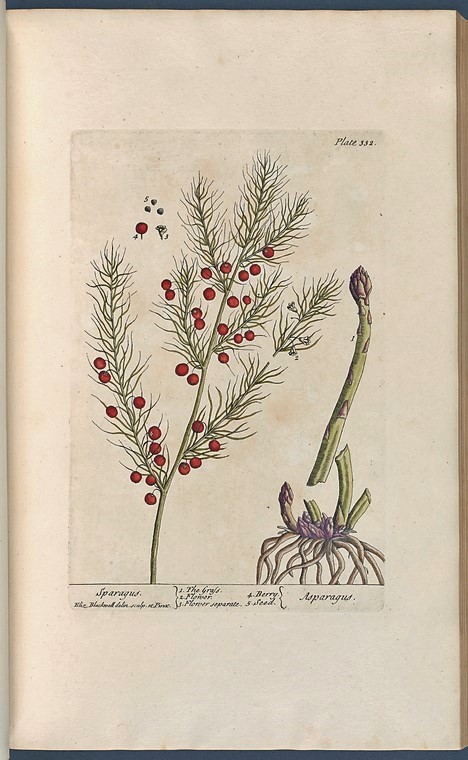

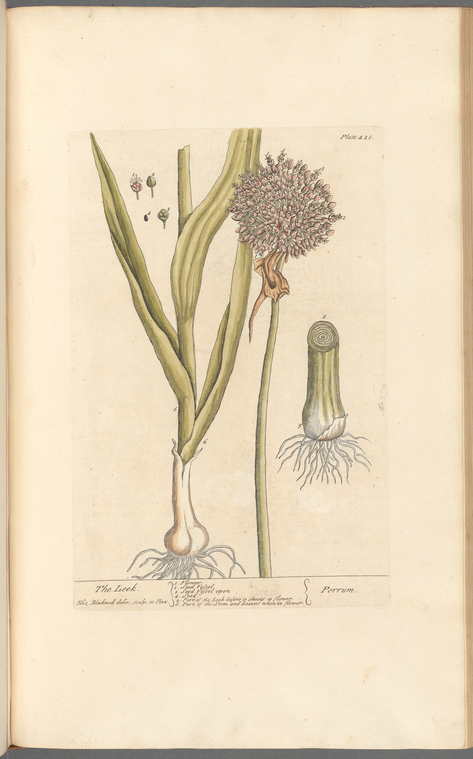

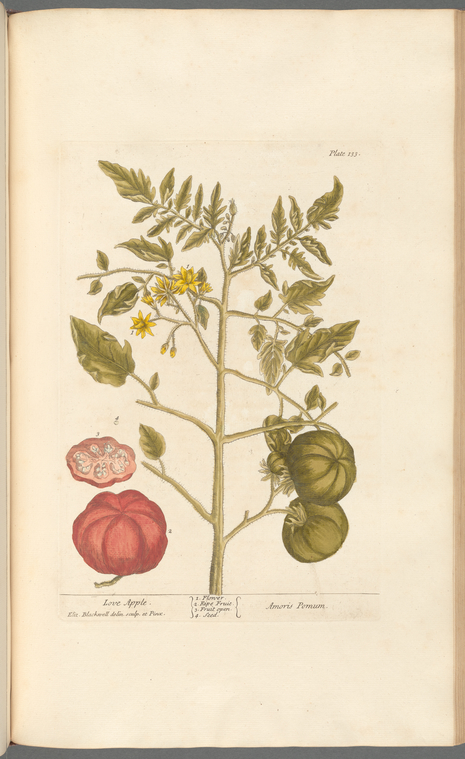

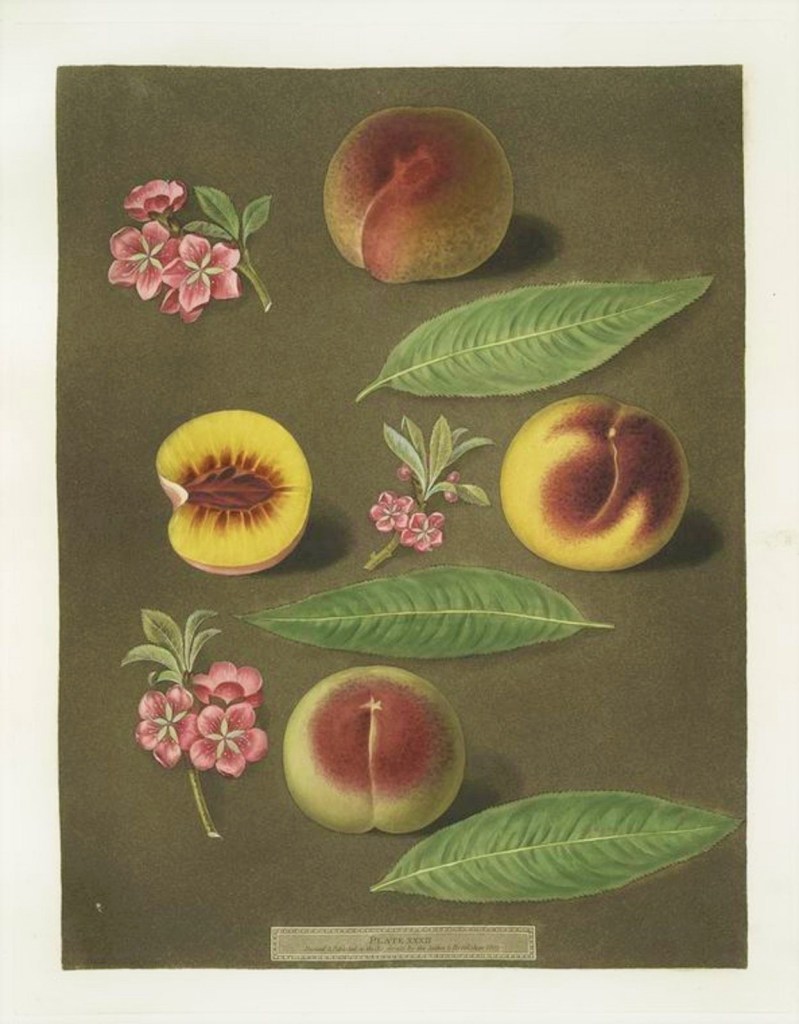

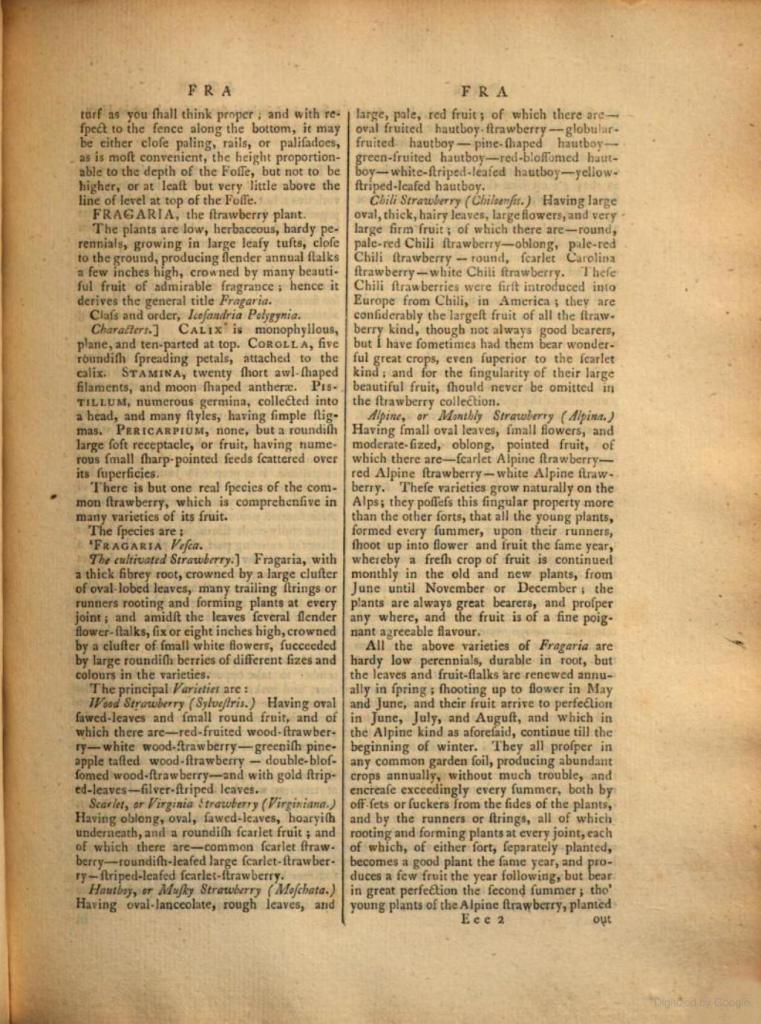

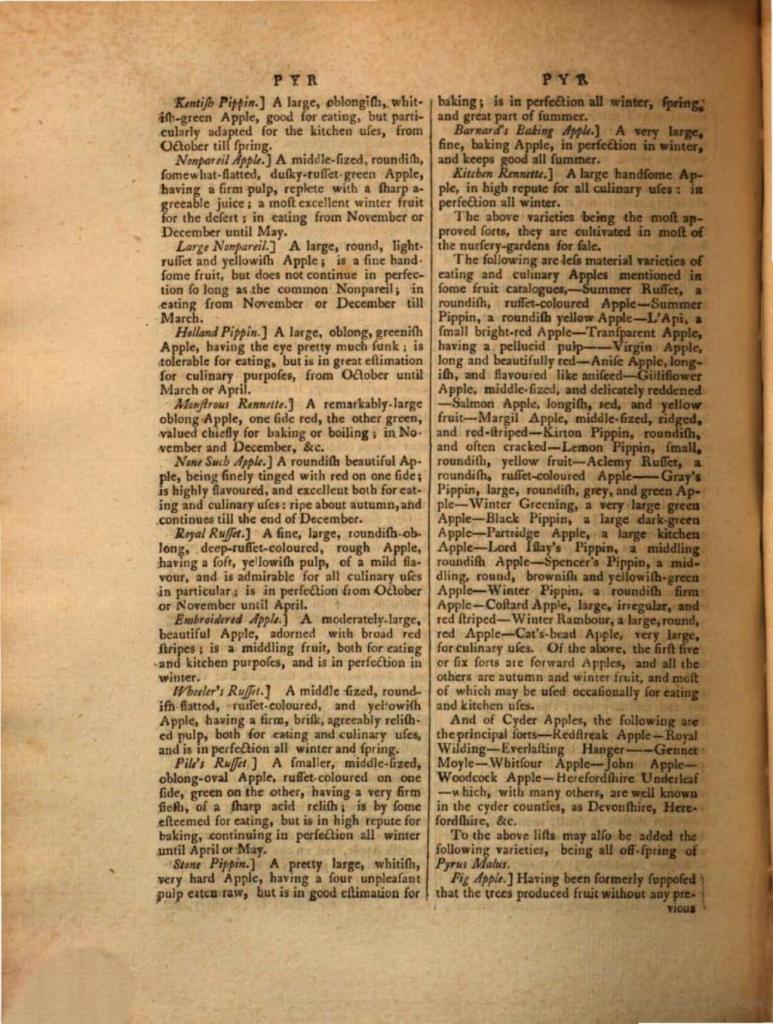

A Note about Illustrations: In her works and letters, Austen mentions almost forty ornamental trees and shrubs that were planted in the shrubbery. On our website, I have previously catalogued Austen’s trees and shrubs with the relevant quotations that mention that shrub or tree and photographs of what the plants look like now (see Austen’s Trees and Shrubs A-K and Austen’s Trees and Shrubs L-Z). For the current blog, I collected Georgian and Regency-era botanical illustrations of all those plants, some of which are used in the header image (Illustration 1 in the Illustration Credits) and all of which are shown in Illustration 2 and 3. A separate Illustration Credits is available at Shrubbery Illustration Credits , and it includes links to the full-size botanical illustrations used here. All the botanical images used are in public domain.

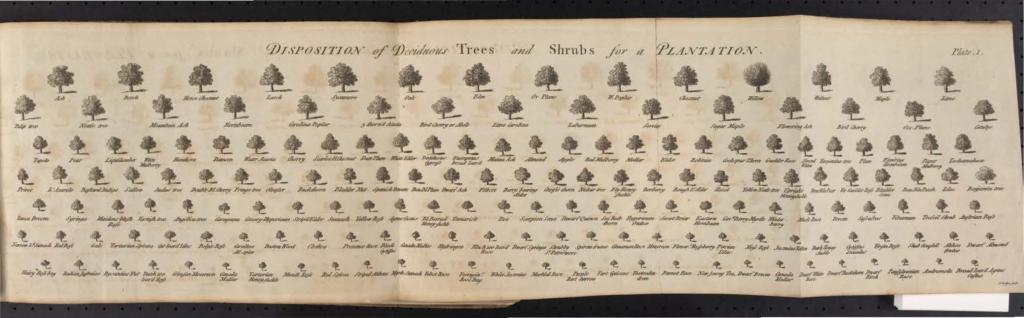

Illustration 2 Trees and Shrubs Over 30 Feet and Illustration 3 Trees and Shrubs Under About 30 Feet

Section I What Did Shrubberies Look Like throughout the Year?

“Our young Piony at the foot of the Fir tree has just blown & looks very handsome; & the whole of the Shrubbery Border will soon be very gay with Pinks & Sweet Williams, in addition to the Columbines already in bloom. The Syringas too are coming out.” Jane Austen’s Letters, Wednesday 29 May 1811 from Chawton to Cassandra

“It was hot; and after walking some time over the gardens in a scattered, dispersed way, scarcely any three together, they insensibly followed one another to the delicious shade of a broad short avenue of limes, which stretching beyond the garden at an equal distance from the river, seemed the finish of the pleasure grounds.” Emma 390-391

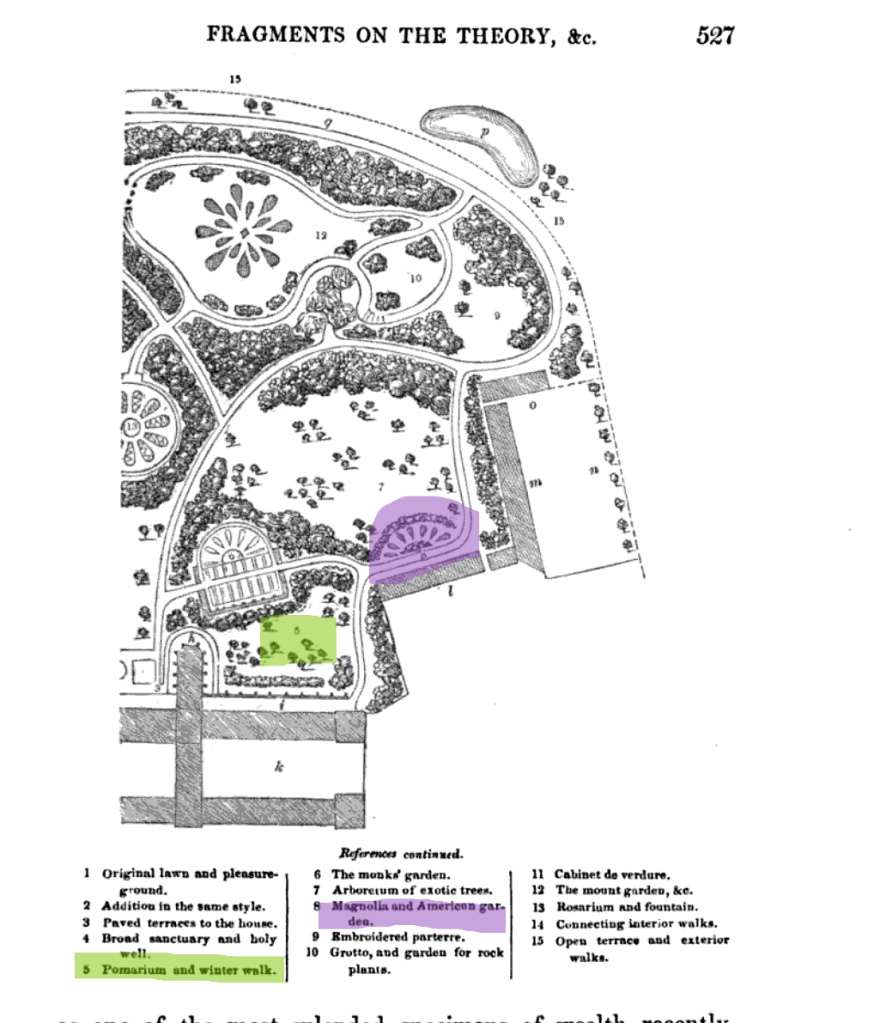

In the novels, we do not get much detail about what a shrubbery looks like, although there is some sense of how extensive they are in different settings. In Austen’s letters, we get more information about the shrubs, trees, and flowers that grow in the shrubbery, as well as a sense of their dimensionality, as we see in the quotation above from Austen’s letter when living at Chawton. Shrubbery could be borders around a lawn or meadow (as at Henry Tilney’s parsonage, Woodston, where the shrubbery is “round two sides of a meadow” NA 221); clumps of shrubs and flowers on a grass lawn; or bigger plantings with serpentine paths through them on larger estates. Shrubberies were typically located near the house for easy access. [For example, Illustration 4-1, below, from Repton in 1816 of Cobham Hall, Kent, shows shrubberies (highlighted in green) interspersed in a large plantation of trees surrounding the house, and the kitchen garden (highlighted in purple) is located near the house, stables, and shrubbery].

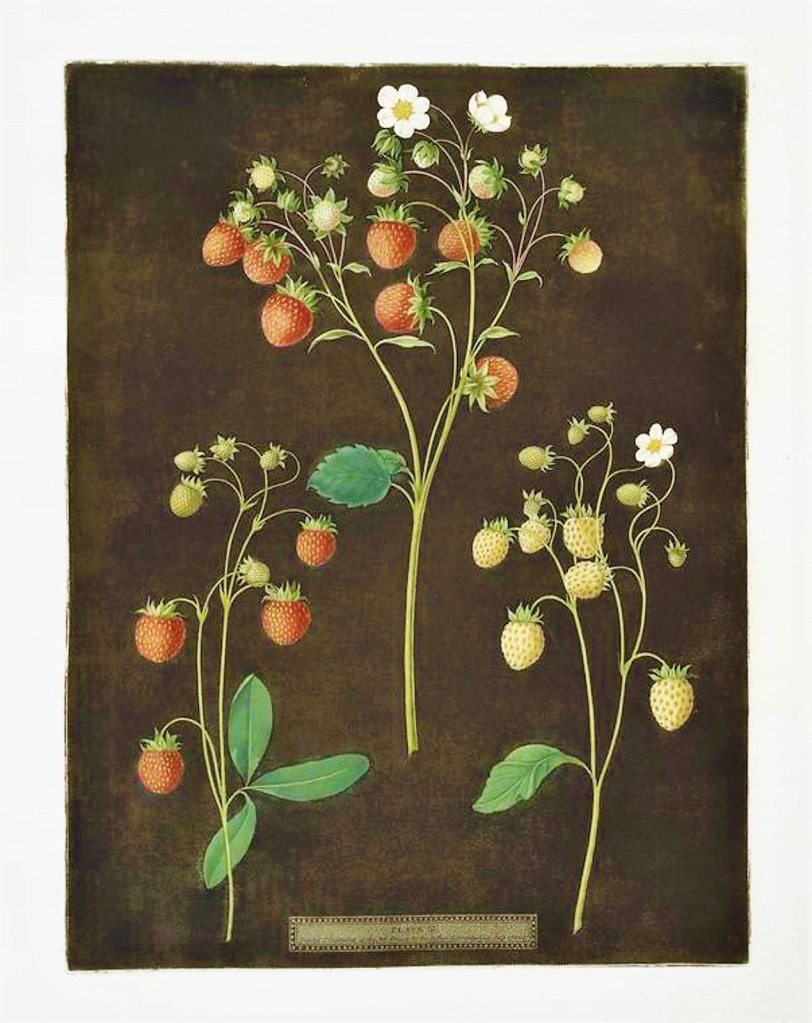

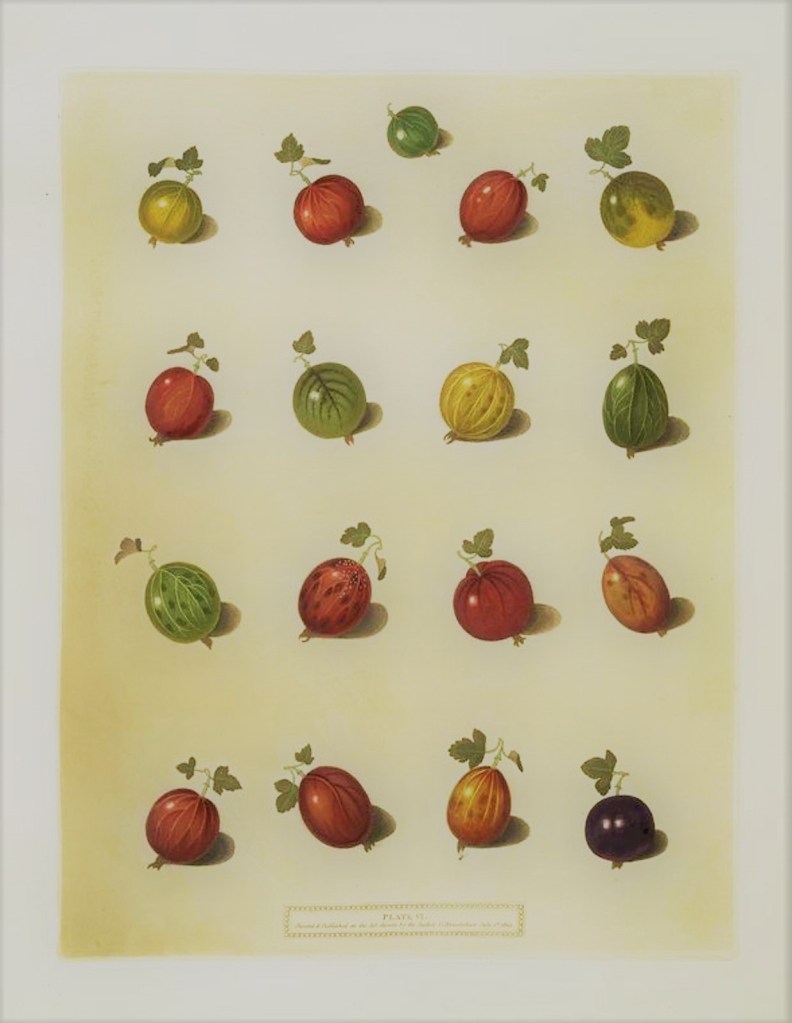

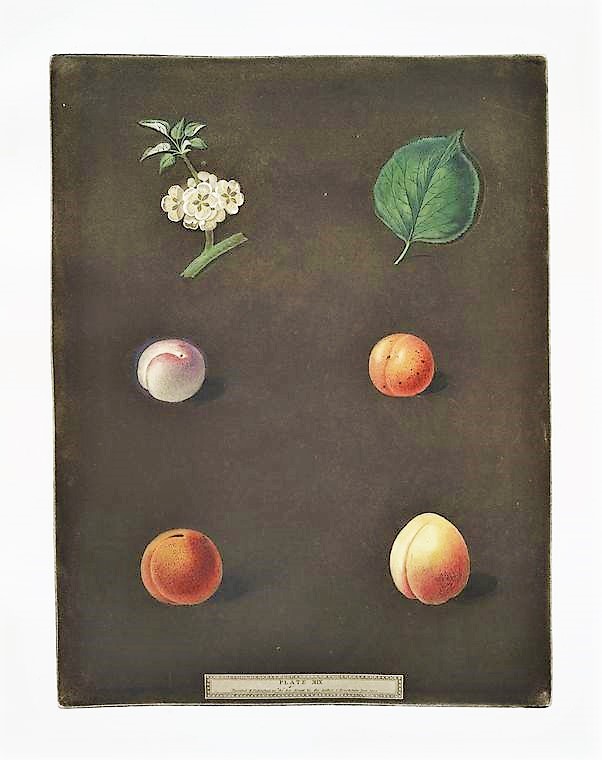

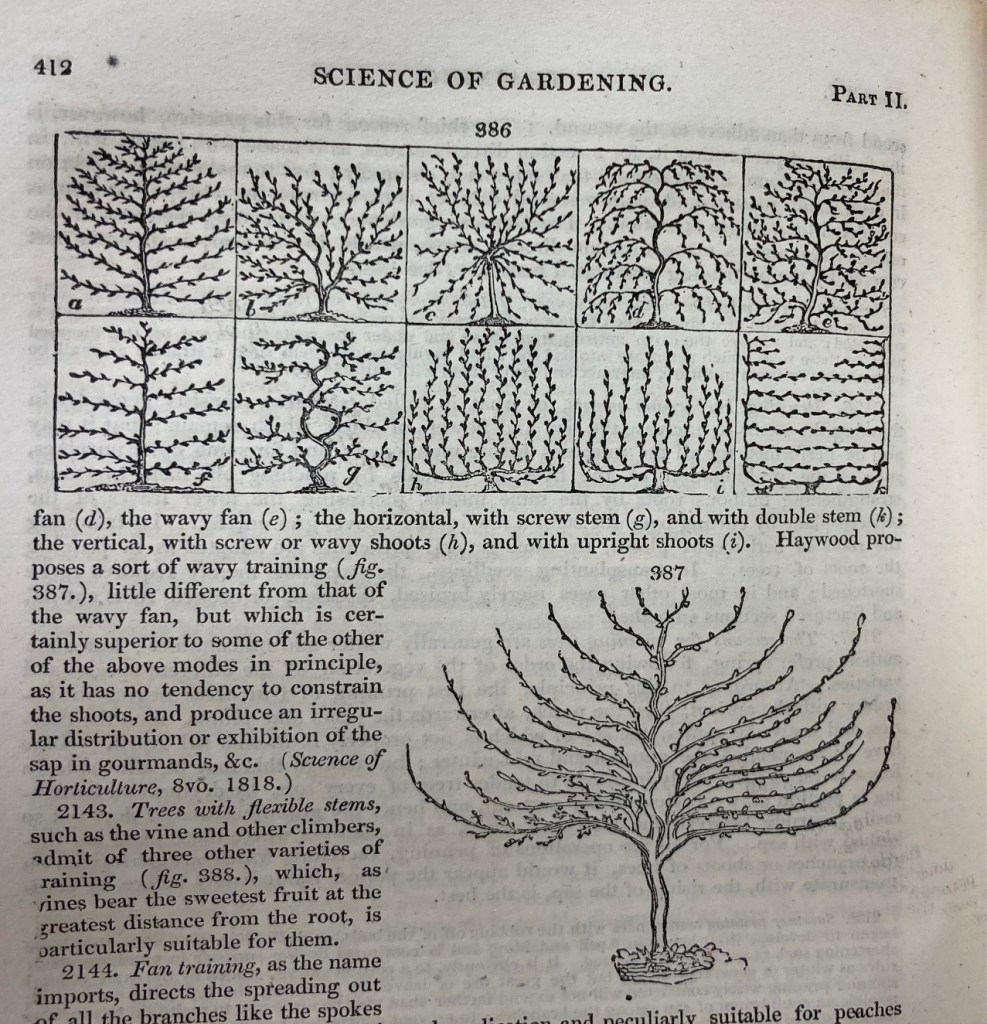

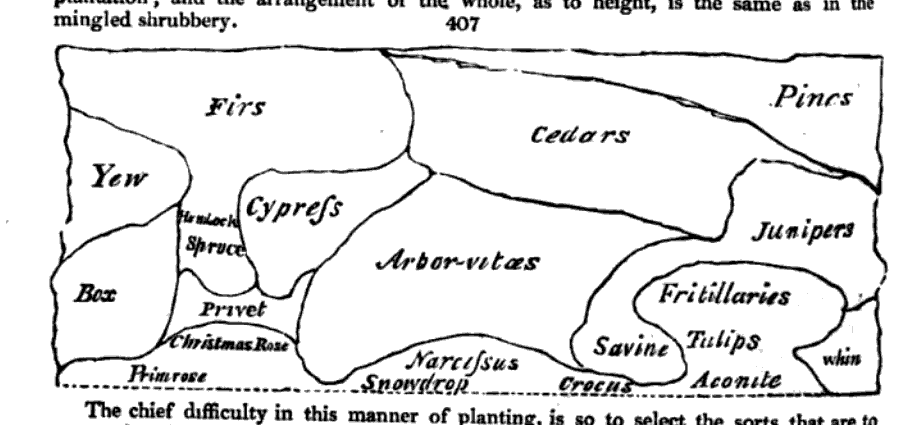

Shrubberies were almost always planted in the “theatrical” manner, with shorter plants in front and taller plants behind, sometimes many rows deep (see the header illustration for an example.) For taller shrubs, increasing space was allowed between rows (and within the row between plants) and it was recommended to have about 10 feet or more between rows of trees (Loudon 1006-7), so that larger plants had space to grow. Thus, on large estates, the shrubbery border could be over sixty feet wide if there were ten rows with 6 rows of shrubs and 4 rows of trees. In 1779, James Meader created two illustrations of deciduous and evergreen shrubs and trees ranked in rows by height to tell planters where in the shrubbery to locate a specific plant (Illustration 4-2 and 4-3, below) and he includes almost every shrub and tree mentioned by Austen. I created two similar pictures in color using botanical illustrations for each of the trees and shrubs mentioned in Austen’s works and letters, grouped by height, in descending order (Illustration 2 Trees and Shrubs Over 30 Feet; Rows I, II, III and Illustration 3 Trees and Shrubs Under About 30 Feet; Rows IV, V, and VI, above). Table 1 (below) corresponds with Illustration 2 and 3 and lists all the trees and shrubs mentioned by Austen that are used for ornamental purposes in the pleasure grounds in order from tallest to shortest, along with details about the current scientific name, the works where Austen mentions the plant, whether it is deciduous or evergreen, the month and color of blooms (using English Regency-era or slightly later sources), and whether it is native to the UK or the year it was first imported.

Table 1 Ornamental Trees and Shrubs Mentioned in Austen’s Works

The shrubbery border could include herbaceous flowers in the front but often was just woody flowering shrubs and ornamental trees. Shrubberies were often planted in the “mingled” manner with a variety of colors, blooming times, and whether a plant was deciduous or evergreen (Loudon 1006). Similar to how kitchen gardens were planted, the aim for shrubberies was to have as many different varieties blooming and in leaf for the longest time. For very large shrubberies, Loudon (1006-1007) suggested varying the month of blooming (6: March to August), color of bloom (4: red, yellow, white, purple), and evergreen or deciduous alternated within each row of plants grouped by height, which results in as many as 48 different plants in one row, although typically evergreens would have to be repeated, since there are fewer evergreens compared to deciduous plants (by a 1 to 12 ratio according to Loudon). Plants could also be planted in the “massed” manner, where several plants of all one kind were grouped together, although still in graduated heights (see Illustration 4-4, below, from Loudon of various evergreens arranged to show a variety of colors of green and texture of foliage 1008). Laird notes that the front row of the shrubbery often included unusual imports or plants that were especially beautiful, noting how on Meader’s evergreen plantation there were taller exotics from North America and Southern Europe mixed in with the shorter evergreens: “Meader’s ranking of the various plants is more intelligible as an equation of height multiplied by either beauty or rarity, cost or singularity” (250).

To see what shrubberies looked like in Austen’s lifetime, pictures of Audley End House offer excellent examples (see Laird 341-4). Illustration 4-5 (below) is an image from William Watts’ The Seats of the Nobility and Gentry (1779; a book that also features Edward Austen’s home Godmersham Park and was in his library), which shows Audley End House in an engraving, with shrubbery and flower beds in the foreground. Audley End was built in the early 1600s in Saffron Walden, Essex and is also featured in a series of full color paintings by William Tomkins in 1788 that shows shrubbery and gardens in several of the pictures (these paintings are privately owned and can be accessed through this link: Art UK Tomkins Link). Click on each painting to see the image and then right click to see a larger image in another tab: Audley End from the Southwest shows acacia trees (black locust, which are mentioned in SS as discussed in Section II) on both sides of the view; Audley End, the Tea House Bridge shows a tea house overlooking water with shrubbery on the sides; Audley End, View from the Tea House Bridge shows more shrubbery, including orange trees in pots sunk into the shrubbery (see Section IV); Audley End and the Ring Hill Temple and Audley End and the Temple of Concord both show temples in the landscape (see Section IV).

Shrubberies were used year-round in the Regency, even Mr. Woodhouse takes his “three turns—my winter walk” (E 61). The walks in the shrubbery were often gravel or sand, or occasionally grass (see Loudon 1006) to ensure good drainage in rain or snow. Loudon recommends shrubbery walks of one to two miles for exercise, starting close to the house, and planting on one side for views, and using circuitous rather than straight lines (1005-6). Recall that when Sir Thomas sends Fanny to the shrubbery after Mr. Crawford’s rejected proposal, it is early January (MP Chapman Edition “The Chronology of Mansfield Park” 555). He tells her: “I advise you to go out: the air will do you good; go out for an hour on the gravel; you will have the shrubbery to yourself, and will be the better for air and exercise” (MP 371). In Northanger Abbey, after Catherine has been at the Abbey several days and when Henry is away, she became “tired of the woods and the shrubberies–always so smooth and so dry” (218) even though it is still winter. Landscape gardener Humphry Repton often included specific “winter garden[s]” that were in sheltered areas near the house as part of his plans for large estates (see Illustration 4.6 and 4.7 of Repton’s map for Ashridge, with a winter garden highlighted in green on Illustration 4.7. A color map from the Red Book for Ashridge shows the same areas labeled more clearly (see the Resources list at the bottom of the blog for “Hardy Plants and Plantings for Repton and Late Georgian Gardens [1780–1820]”; the Ashridge map is on page 23 of the PDF.) When shrubberies were planned, care was taken to be sure that at least some of them could be used in all seasons.

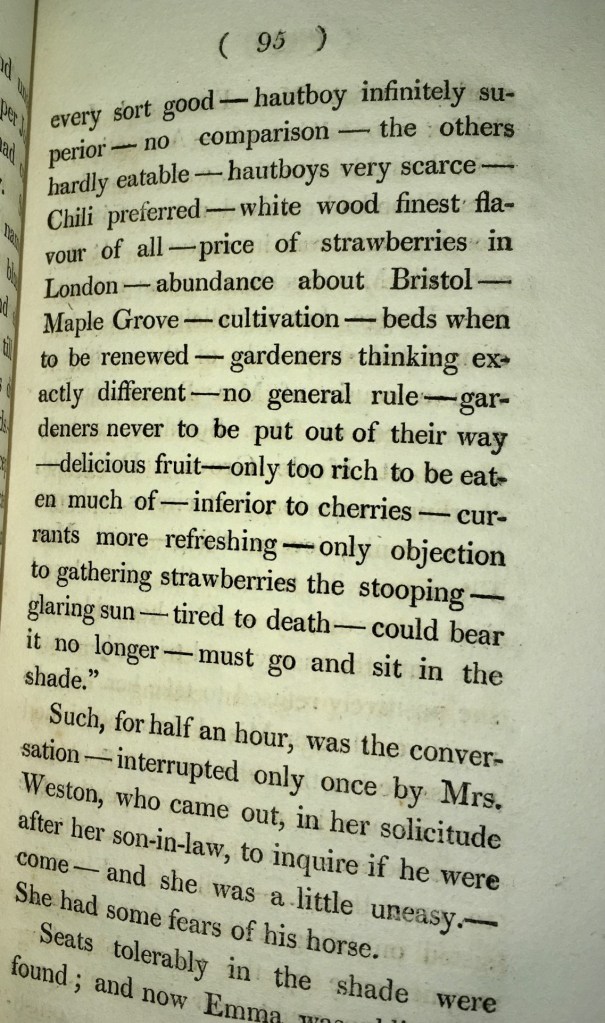

Illustration Set 4 Miscellaneous Shrubbery Prints

In several of her letters to Cassandra, Austen focuses on what is blooming or fruiting in the garden, as in the letter above which mentions the “piony”. About half of the trees and shrubs mentioned by Austen bloomed in May in England (see Table 1), similar to the effusion of blooming that happens in May in Eastern Washington. In Emma, the characters seem to be especially attuned to the seasonal changes in nature: for example, in February, Emma wonders if the elder will be coming out soon, foretelling spring (E 203). When the Highbury folks go to Donwell Abbey “at almost Midsummer” (388) and walk to the avenue of lime trees, it is important to know that limes in England (called lindens in the United States) bloom right around the time of the strawberry picking party (June 23, see the Chapman Edition, “The Chronology of Emma” 497). At midsummer on a hot sunny day, lime trees would be a heady perfumed mass of yellow flowers surrounded by buzzing bees (Miller 174; see video 1). Emma’s use of the word “delicious shade” (390) for the avenue of limes reflects the full sensory experience of limes in bloom. When Emma has joined Mr. Knightley and Harriet in the lime avenue and “They took a few turns together along the walk.—The shade was most refreshing, and Emma found it the pleasantest part of the day” (392), Austen highlights the natural and emotional harmony available for Emma with Mr. Knightley at Donwell Abbey.

Section II What Plants Were Valued in the Georgian and Regency Shrubbery?

Cleveland was a spacious, modern-built house, situated on a sloping lawn. It had no park, but the pleasure-grounds were tolerably extensive; and like every other place of the same degree of importance, it had its open shrubbery, and closer wood walk, a road of smooth gravel winding round a plantation, led to the front, the lawn was dotted over with timber, the house itself was under the guardianship of the fir, the mountain-ash, and the acacia, and a thick screen of them altogether, interspersed with tall Lombardy poplars, shut out the offices.” Sense and Sensibility 342-343.

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny, in reply. “My uncle’s gardener always says the soil here is better than his own, and so it appears from the growth of the laurels and evergreens in general. The evergreen! How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen! When one thinks of it, how astonishing a variety of nature! In some countries we know the tree that sheds its leaf is the variety, but that does not make it less amazing that the same soil and the same sun should nurture plants differing in the first rule and law of their existence.” Mansfield Park 244

Fanny’s rhapsody on the common laurel (Prunus laurocerosus) makes sense in the context of the rarity of native evergreens in Britain and the frequent use of imported evergreens in the shrubbery. Marshall notes that laurel is “the stock plant in shrubberies and other ornamental grounds” (318) and is an import from around the Black Sea (311). Laurel is mentioned twice in Mansfield Park, at the Mansfield Parsonage (244) and in the wilderness at Southerton (106); Mrs. Elton notices the laurel at Hartfield “[s]o extremely like Maple Grove!” (E 294); and there is a laurel hedge at the Collins’ Hunsford parsonage (PP 176). According to Laird, there are seven native British evergreens: yew, holly, box, juniper, spurge laurel, butchers broom, and Scots pines (393, note 36). Four of these native evergreens are mentioned by Austen, sometimes connected with a garden: Mrs. Jennings mentions that there is an ”old yew arbour” at Delaford (SS 223) and in Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford mentions yews around a farm house when he was lost and stumbled on Edmund’s future parsonage (280); a holly branch helps to hide Anne in the hedgerow where she overhears Captain Wentworth talking to Louisa (P 95); Box Hill of Emma fame (399) is named after the “extensive plantations of box” (Marshall 91) that grow there; and the “thick grove of old Scotch firs” in Northanger Abbey that attract Catharine are Scots pines (183). Other evergreens that Austen mentions that were imported include spruce, fir, lavender, and myrtle (see Table 1). Evergreens were especially valued both for timber and for the year-round green color in the pleasure grounds.

Laird (especially 61-98) details the explosion of interest in England for American plants in the 1700s, especially flowering trees or shrubs that were also broadleaf evergreens, such as evergreen magnolias, rhododendrons, azaleas, and mountain laurel (kalmia). There is an Austen connection for the use of American exotics as Laird reports that nursery bills for James Leigh, the cousin of Jane Austen’s mother, at Adlestrop in 1762-63 show orders for many American exotics including rose acacia (Robinia hispida), Hydrangea, New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), Catalpa bignoniodes, a Magnolia grandiflora, and Rhododendron maximum (156-157). Jane and her family visited their family cousin the Rev. Thomas Leigh at Adlestrop Parsonage in 1806 after the improvements of Humphry Repton in 1799 at the parsonage and Adlestrop for Rev. Leigh and James Leigh’s son, James-Henry, who was the current owner of Adlestrop (Batey 81; Letters Biographical Index “Leigh families” 548-49) and these American exotics would be mature trees by then. Repton’s plan for the Ashridge gardens includes a Magnolia and American garden (Illustration 4.7, highlighted in purple, above). Harvey estimated that once a tree or shrub was imported to London or large estates, it would take about 20 years for the trees to get out to the smaller planters in the country. The acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia; sometimes also called false acacia) mentioned at the Cleveland estate in Sense and Sensibility was an import from America (where it is called black locust) which Abercrombie says does well in open plantings in England and was valued for its sweet smelling, pendulous blossoms (ROBINIA). The English also imported American maples such as the sugar maples and scarlet maples (Laird 86) that were much taller trees than the native English or field maple. I think that the maples at Mrs. Elton’s nouveau riche brother-in-law’s seat, Maple Grove, in Emma were the tall imports from America for the grandest effect. Marshall mentions many American varieties of English native trees that were also grown in the shrubbery and ornamental woods, such as American limes (or lindens, 413); oaks, including the evergreen live oak as well as the white, red, and black oaks (311); and many conifers, which were all classed as Pinus at that time, such as Weymouth or white pine, Newfoundland spruce fir, and Hemlock-fir (282-283). Laird examined bills from nurserymen for large estates and found in the mid to late 1700s that orders would include “large quantities of evergreen and flowering shrubs bought in bulk” (50-100 plants) such as laurels, hollies, lilacs, syringas, roses, laburnums, and honeysuckles among others and then “the very small quantities of special plants bought as curiosities”, which often included more expensive imports from America (152). Because America had a similar temperate climate to England in many parts of the America of the 1700s, trees and shrubs from America could be grown outdoors and did not need as much winter protection as did imports from more tropical locales.

Section III How Are Shrubberies Used in Austen’s Works?

“The weather continued much the same all the following morning; and the same loneliness, and the same melancholy, seemed to reign at Hartfield—but in the afternoon it cleared; the wind changed into a softer quarter; the clouds were carried off; the sun appeared; it was summer again. With all the eagerness which such a transition gives, Emma resolved to be out of doors as soon as possible. Never had the exquisite sight, smell, sensation of nature, tranquil, warm, and brilliant after a storm, been more attractive to her. She longed for the serenity they might gradually introduce; and on Mr. Perry’s coming in soon after dinner, with a disengaged hour to give her father, she lost no time in hurrying into the shrubbery.” Emma 462.

“Reginald is never easy unless we are by ourselves, and when the weather is tolerable, we pace the shrubbery for hours together.” Lady Susan, Letter 16 Lady Susan to Mrs Johnson MW 268

Shrubberies are places where characters go for outdoor exercise, for self-reflection and soothing, or to have the privacy to meet romantic partners or to discuss important personal events with family or friends. At Netherfield, Mr. Darcy and Miss Bingley walk in the shrubbery without any romantic intent, at least on Mr. Darcy’s side, and he tries to accommodate both Elizabeth and Mrs. Hurst into the walk when they meet them, also out walking, on a narrow path (PP 57-58). Catherine and Eleanor enjoy walking in the shrubbery at Northanger Abbey (218). Even indolent or invalid characters enjoy their sheltered spaces–Mr. Woodhouse “never went beyond the shrubbery, where two divisions of the grounds sufficed him for his long walk, or his short, as the year varied” (E 25) and Lady Bertram tells Mr. Rushworth she likes to get “’out into a shrubbery in fine weather’” (MP 65).

Both Fanny and Emma use the shrubbery for reflection and to soothe themselves when troubled, and shrubberies afford them the privacy to have important conversations there with the men they will marry. When Emma is distressed about the possibility that Mr. Knightley will marry Harriet and tries to fully understand “the blindness of her own head and heart!—she sat still, she walked about, she tried her own room, she tried the shrubbery. . .” (E 448), and eventually she acknowledges her errors and realizes the depth of her love for Mr. Knightley. Fanny is eager to follow Sir Thomas’s advice to go to the shrubbery after he has berated her for rejecting Henry Crawford (MP 371). Later, she avoids walking alone in the shrubbery to avoid a scolding by Mary Crawford. who is angry that Fanny has rejected Henry (412). Edmund is sent by Sir Thomas to talk to Fanny in the shrubbery, and Edmund wants her to “open her heart to” him, to “have the comfort of communication” (399). Although Edmund does not understand the depths of Fanny’s distrust of Henry, he is aware of her feeling “oppressed and wearied” by their talk and takes her into the house (410). After the rupture with Mary caused by Maria’s elopement with Henry Crawford, Edmund recovers emotionally by “wandering about and sitting under trees with Fanny all the summer evenings” (535), and eventually he realizes that he loves her romantically. Both the heroes and the heroines can find solace with others in the shrubbery.

Shrubberies are especially associated with newly married couples and those getting engaged. In Mansfield Park and Northanger Abbey, the parsonage where each heroine will ultimately live is described as having a young shrubbery about “half a year” old (NA 221) or of three years growth (from when the Grants moved into the parsonage; MP 243). The “project[ing of] shrubberies” is one of the activities of the newly married Elinor and Edward (SS 425). Shrubberies are also places where engaged lovers can have privacy, such as when Jane and Bingley escape to the shrubbery to avoid Lady Catherine (PP 389). Lady Susan and Reginald “pace the shrubbery for hours together” in Lady Susan, and Mrs. Vernon is aghast that it is often in view of Lady Susan’s daughter, whose bedroom overlooks the shrubbery (MW 268, 271). When Emma and Mr. Knightley walk together in the shrubbery after a rain shower in early July (probably July 8 based on the Chapman Edition’s Chronology of Emma 498), they might be enjoying the sight and smell of late June and early July Austen floral favorites such as lime tree blossoms, roses, honeysuckle, lavender, and syringa (Miller 200, 236). After Mr. Knightley consoles Emma for the loss of Frank Churchill, and Emma tries to promote his happiness, even though she imagines he will choose Harriet, they are able to resolve their misunderstandings and declare their love, on their way to “perfect happiness” (E 471).

Section IV Greenhouses and Other Architectural Elements of Pleasure Grounds

“. . .for here are some of my plants which Robert will leave out because the nights are so mild, and I know the end of it will be that we shall have a sudden change of weather, a hard frost setting in all at once, taking every body (at least Robert) by surprise and I will lose every one;” Mansfield Park 247-248

“Miss Bennet, there seemed to be a prettyish kind of a little wilderness on one side of your lawn. I should be glad to take a turn in it, if you will favour me with your company.” “Go, my dear,” cried her mother, “and show her ladyship about the different walks. I think she will be pleased with the hermitage.” Pride and Prejudice 391

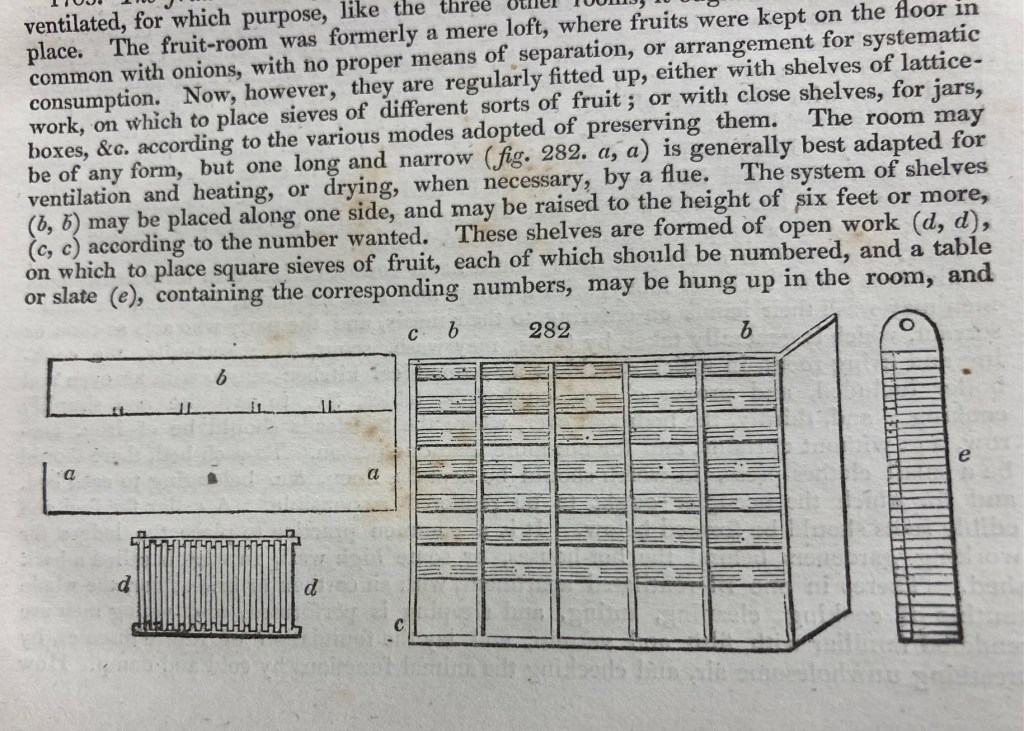

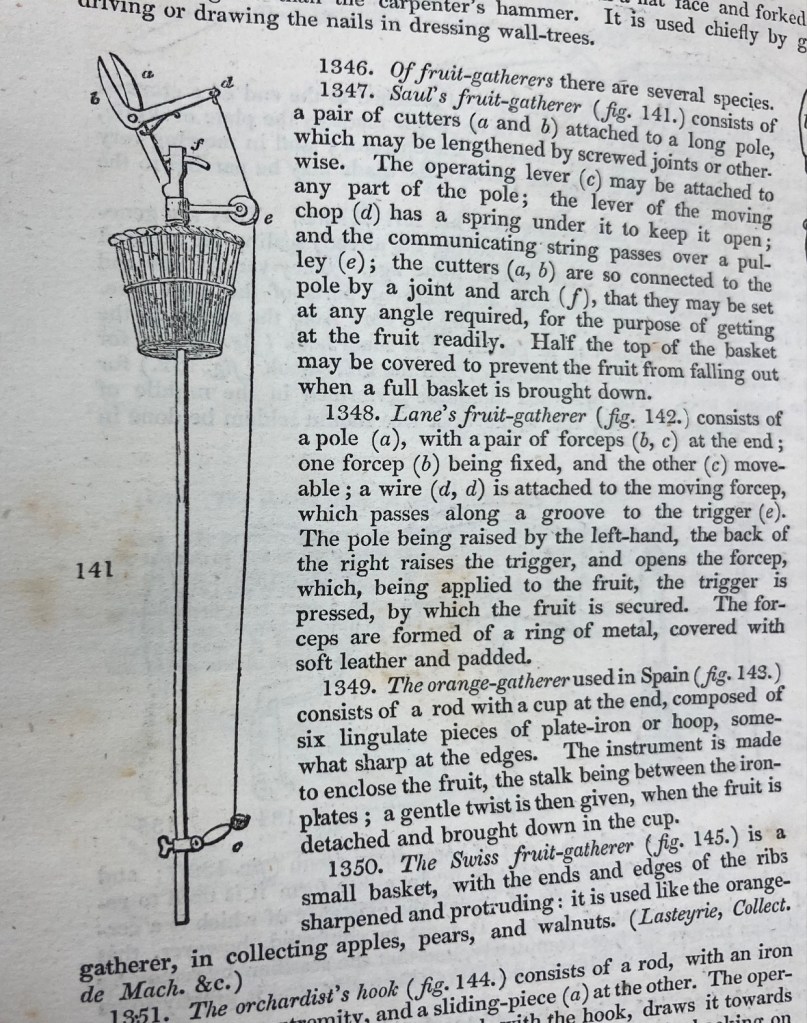

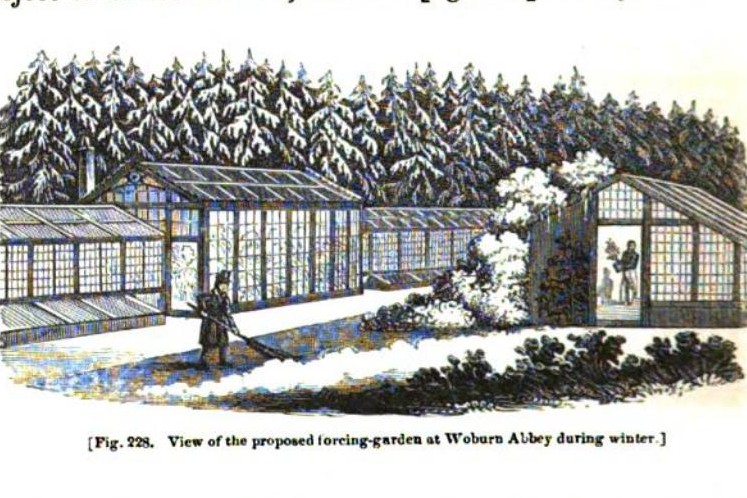

Many gardens had greenhouses for sheltering plants that needed to be protected during the winter and could be heated if the weather were freezing, as Catherine notes about the Allens’ “one small hot-house, which Mrs. Allen had the use of for her plants in winter, and there was a fire in it now and then” (NA 183). A greenhouse is mentioned at Cleveland, when the Dashwood sisters go outside with Charlotte “dawdling through the greenhouse, where the loss of her favorite plants, unwarily exposed, and nipped by the lingering frost, raised the laughter of Charlotte” (SS 343; see Illustration 5.1, below, from Repton of a simple greenhouse). Tropical plants would need much more heat and were kept in hothouses that needed constant heat sources, such as the pinery that General Tilney casually mentions for growing his (very expensive) pineapples (NA 182). Mrs. Grant talks about her gardener leaving her plants out when there is a threat of frost and a few paragraphs later, Mary Crawford states that she plans to be rich enough to purchase as much myrtle as needed (MP 247-48); myrtle is a plant that would have grown in a greenhouse in Northamptonshire, thus clarifying why Mary mentions it (see Abercrombie MYRTUS and Loudon 1094). Laird discussed how greenhouse plants would be taken out of the greenhouses in the summer and sometimes put into the ground in their pots in the shrubbery, especially citrus trees and other showy exotics (see 133-172). Greenhouses were places to grow beautiful plants that needed more protection in winter and that could become places for winter exercise if they were big enough (see Repton Fragments 552). Illustration 5.2, below, shows Repton’s drawing of the forcing houses at Woburn Abbey in winter, perhaps something like what Austen had in mind for the kitchen gardens at Northanger Abbey.

Austen would be familiar with the use of temples and other buildings in landscape gardens through her visits to Godmersham, home to her brother Edward Austen Knight. At Godmersham, “just outside the park was a small rounded hill on top of which, within the woods, was a summer house which had been built by the Knights earlier in the eighteenth century as a Grecian temple in the Doric style with a portico entrance of fluted columns and marble steps, and a fine grassy walk leading up to it” (Le Faye 237-8). Batey has a picture that shows the side of the temple and the view from it across the river Stour to the mansion, and remarks that Austen enjoyed sitting in the temple “where she would think out further plots for her novels” (102). The “Grecian temple” at Cleveland where Marianne tries to imagine seeing Combe Magna, Willoughby’s estate 30 miles distant, and where she plans a “twilight walk” (SS 343-4), is probably modeled on Godmersham’s temple.

In Northanger Abbey, Catherine is lured to a drive with John Thorpe by the prospect of “Blaize Castle”, which Thorpe promises is “the oldest in the kingdom” with “dozens” of towers and long galleries (83). The joke is that Blaise Castle is a “gothic folly” on a hill overlooking Bristol and the nearby river valleys on the Blaise estate built by a “Bristol sugar-merchant. . . in 1766” (NA note 4 325). Lane describes the interior: “The design features three ornate castellated turrets, one of which contains the staircase giving access to the flat roof of the central, lower tower. Traceried windows and cruciform arrow-slits supply the Gothic ornamentation, while stained glass and elegant interior plasterwork supplied the comfort. There was a vestibule and dining room below, and a main chamber above” (79). A later owner of the property commissioned Humphry Repton to change the landscape and Illustration 5.3, below, shows Repton’s watercolor of Blaise Castle from the 1796 Red Book for Blaise. Loudon notes that buildings should be used in the shrubberies “more sparingly, and with greater caution” (1011) than statues or urns and this seems to be an opinion that Austen would concur with.

The hermitage mentioned at Longbourn in Pride and Prejudice reflected an interest in the late 1700s and early 1800s in more natural wooded walks and rustic buildings that would fit into the wooded landscape. “A hermitage, meant to resemble the hut of a religious recluse and to inspire melancholy associations, ought properly to be located in a secluded wooded area, so the Bennets’ hermitage is sited correctly, though perhaps too close to the house for best taste” (Wilson 38). Repton shared an example of a “rustic thatched hovel”, which was used as a place to rest and observe the views in a hilly wooded area and which he recommended should be covered with vines and use tree trunks in the construction (Observations 255-6; Illustration 5.4 below); this building gives a sense of what more rustic landscape architecture looked like. Batey writes that when Jane Austen was living in Chawton, she would have known the hermitage at nearby Selborne that Gilbert White built behind his house The Wakes (44-46). Catherine expresses pleasure in a “sweet little cottage” among “the apple trees” at Woodston, Henry’s parsonage, and the General embarrasses her when he tells Henry it must be preserved (NA 220). Temples, covered seats, and tea houses in gardens were widespread and even less affluent families, like the Martins, yeoman farmers, in Emma, have, in Harriet’s words, “a very handsome summer-house” in their garden “large enough to hold a dozen people” where they plan to drink tea next summer (E 27).

Illustration Set 5 Miscellaneous Garden Architectural Elements

Section V The Shrubbery as an Expression of the Estate Owner’s Taste and Wealth

“As to all that,” rejoined Sir Walter coolly, “supposing I were induced to let my house, I have by no means made up my mind as to the privileges to be annexed to it. I am not particularly disposed to favour a tenant. The park would be open to him of course, and few navy officers, or men of any other description, can have had such a range; but what restrictions I might impose on the use of the pleasure-grounds, is another thing. I am not fond of the idea of my shrubberies being always approachable; and I should recommend Miss Elliot to be on her guard with respect to her flower garden. I am very little disposed to grant a tenant of Kellynch Hall any extraordinary favour, I assure you, be he sailor or soldier.” Persuasion 21

The number of acres contained in this garden was such as Catherine could not listen to without dismay, being more than double the extent of all Mr. Allen’s, as well her father’s, including church-yard and orchard. The walls seemed countless in number, endless in length; a village of hot-houses seemed to arise among them, and a whole parish to be at work within the enclosure. The general was flattered by her looks of surprise, which told him almost as plainly, as he soon forced her to tell him in words, that she had never seen any gardens at all equal to them before; and he then modestly owned that, “without any ambition of that sort himself — without any solicitude about it — he did believe them to be unrivalled in the kingdom. If he had a hobby-horse, it was that. He loved a garden. Though careless enough in most matters of eating, he loved good fruit — or if he did not, his friends and children did. There were great vexations, however, attending such a garden as his. The utmost care could not always secure the most valuable fruits. The pinery had yielded only one hundred in the last year. Mr. Allen, he supposed, must feel these inconveniences as well as himself.” Northanger Abbey 182

The shrubbery and woods of the pleasure ground was the domain of men for planning the design for planting but open to women for exercise. Sir Walter clearly distinguishes that his area of control is the shrubbery and park, and Elizabeth’s area of control is the flower gardens (P 21). Laird’s review of many different estates from 1700-1800 shows that the male estate owner was the person to whom shrubbery plans and follow-up questions were addressed by landscape gardeners (e.g., the Duke of Argyll at Whitton 83-88 or Lord Petre at Thorndon Hall 63-67), although there are some exceptions, like widows (the Duchess of Portland at Bulstrode 221) or times when the married couple is both addressed and the wife appears to play a role in decisions about pleasure grounds and not just flower gardens (the Duchess and Duke of Portland before his death in 1762 or the Duke and Duchess of Beaufort at Badminton 128). Since men were the predominant property owners in Austen’s time, except for widows like Lady Catherine de Bourgh, it makes sense that they would be the ones to make decisions about the pleasure grounds and the park.

When Catherine explores the shrubbery and kitchen garden with Eleanor and General Tilney, General Tilney is telling her that he is a VERY rich man in detailing his garden woes. If his gardens are “unrivalled in the kingdom”, that is a big claim considering how much royalty and aristocrats spent on landscape gardens. Natali details the ways in which the General’s off-hand comment that his pinery “yielded only one hundred in the last year” tells someone in the know the vast sums he has spent on pineapple plants to produce 100 pineapples because the plants required being kept in a hothouse with constant heat throughout the year, and each plant took 2-3 years to produce one pineapple. “By pointing to his pinery, General Tilney is asserting that he is not only a man of monetary value but also a man of social value. Readers would have instantly recognized that General Tilney’s wealth would perhaps have rivaled that of the highest, wealthiest, and most influential group of land-owning aristocrats in England.” Although the General is focused on the expense of his kitchen gardens rather than his pleasure grounds in this example, pleasure grounds were also places to spend lots of money in the Regency era, especially by importing many rare trees and shrubs that needed expensive care.

Discussions of taste pervade the Regency-era literature on landscape gardening; “taste” is mentioned 100 times in Repton’s collected works and Loudon describes Repton in the introduction as “eminent for his artistical genius and taste” (1840 xii). Repton compliments the good taste of his royal or noble and wealthy clients, including the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Portland, and the Earl of Darnley (364, 141, and 418). When Elizabeth explores Pemberly, she forms a favorable opinion about the taste and values of Mr. Darcy in a way that corresponds with the Georgian and Regency focus on gardens and landscape grounds as an expression of the owner’s taste. The language that Elizabeth uses when she sees Pemberly reflects her sense of Darcy’s good taste: “. . . in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste.” (PP 271). Later when Elizabeth and Mrs. Gardiner visit Georgianna, the view is beautiful and the trees have special meaning: “Its windows opening to the ground, admitted a most refreshing view of the high woody hills behind the house, and of the beautiful oaks and Spanish chestnuts which were scattered over the intermediate lawn.” (295). Oaks and Spanish chestnuts are noted by Repton to be preferred for English landscapes rather than quicker-growing larches and spruce firs which are grown for profit (Fragments 46). Marshall notes that the Spanish or sweet chestnut grows to “a great height” and is good as an ornamental (167). He also goes on at length about the historical importance of oaks to England, especially for shipbuilding “the oak raised us once to the summit of national glory” and comments on its beauty as an ornamental tree as well (314). Because oaks take so long to attain full maturity, growing them is a commitment to the future and reflects Mr. Darcy’s stability as well as his taste and Englishness.

Critics of Austen’s work note that small details reveal much when you understand the historical and cultural context, as the annotations in the Cambridge editions of the six novels (2005-2006) attest. In the Regency era shrubberies were constructed with a large variety of trees and shrubs from America and Europe as well as England, presented “theatrically” in ascending height. Plants were chosen to bloom for as long as possible and included many evergreens since the shrubbery was used year-round. In the novels, shrubberies are important places for Austen’s heroines to experience nature, exercise, reflect, and most importantly, to have privacy for important conversations away from other family members. Pleasure grounds and other landscape elements revealed the wealth and taste of the owner and included architectural elements as places to enjoy views, rest, and, perhaps, take refreshment.

RESOURCES

For more information about Humphry Repton, color pictures from some of his Red Books, as well as an extensive list of what trees and shrubs were popular in the late 1700s and early 1800s pleasure grounds, see Sarah Rutherford’s 2018 research report “Hardy Plants and Plantings for Repton and Late Georgian Gardens (1780–1820)” for Historic England, which is available for download at: Repton Research Report from Historic England.

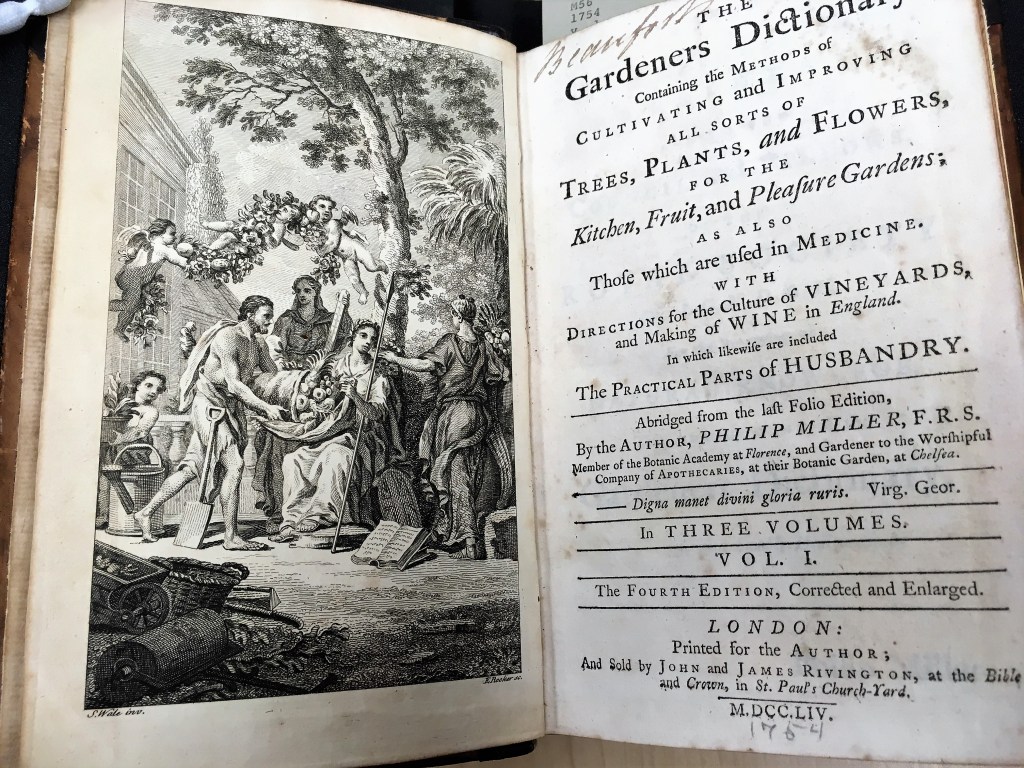

Historian Andrea Wulf has written several engaging and accessible books about the history of English landscape gardening and its cultural impact. This Other Eden: Seven Great Gardens and 300 years of English History by Andrea Wulf and Emma Gieben-Gamal (2005) details gardens at Hatfield House, Hampton Court, Stow, Hawkstone Park, Sheringham Park, Chatsworth, and Hestercombe from the 1600-the early 1900s. The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire and the Birth of an Obsession (2008) explores the relationship between American John Bartram and Englishman Peter Collinson that brought many American plants to England; the rivalries between Philip Miller, one of England’s foremost botanists for decades, and other botanists, including Carl Linnaeus, for whose vision would shape eighteenth century botany; and the explorations of Australia and other parts of the south Pacific by Captain Cook with botanist Joseph Banks and others. The Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation (2011) examines the impact of the English landscape garden movement on our first four presidents in their design of their own gardens and plans for the country.

In the Works Cited list, I highly recommend Mavis Batey‘s and Kim Wilson’s books. Both have beautiful photographs and explore many aspects of Jane Austen and Landscape Gardening.

WORKS CITED

Note: Several of the works cited here were owned by Edward Austen Knight at Godmersham. See https://www.readingwithausten.com/catalogue.html for the full 1818 catalogue of works in his library.

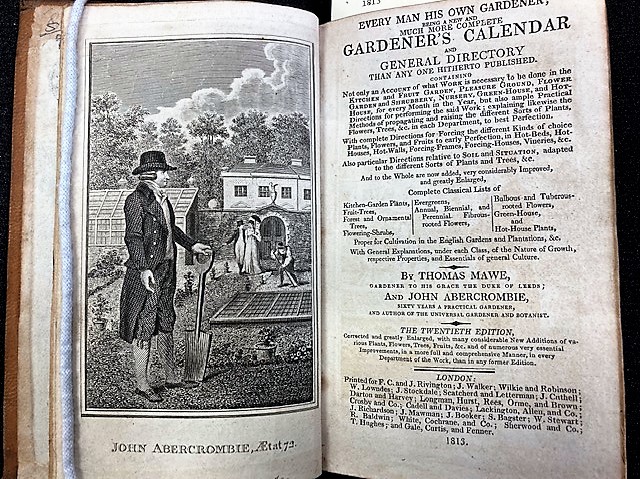

Abercrombie, John. (Also lists Mawe, T. as an author but he did not contribute). The Universal Gardener and Botanist London: G. Robinson, Pub., 1778. This is the same edition that Edward Austen Knight owned. Digitized by the Ohio State University: Abercrombie Universal Gardener

Austen, Jane. Emma. Eds. Richard Cronin & Dorothy McMillan. Cambridge: CUP, 2005.

____. Emma. Appendices: “Chronology of Emma.” Ed. R. W. Chapman, 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1953/1967. . Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

____. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

____. Juvenilia. Ed. Peter Sabor. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

____. Mansfield Park. Ed. John Wiltshire. Cambridge: CUP, 2005.

____. Mansfield Park. Appendices:“Chronology of Mansfield Park”. Ed. R. W. Chapman, 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1953/1967.

____. Minor Works. Ed. R. W. Chapman, 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1953/1967.

____. Northanger Abbey. Eds. Barbara M. Benedict & Deidre Le Faye. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

____. Persuasion. Eds. Janet Todd & Antje Blank. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

____. Pride and Prejudice. Ed. Pat Rogers. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

Batey, Mavis. Jane Austen and the English Landscape. London: Barn Elms, 1996.

Harvey, John H. The Availability of Hardy Plants of the Late Eighteenth Century. Glastonbury, UK: Garden History Society, 1988.

Laird, Mark. The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds 1720-1800. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

Lane, Maggie. “Blaise Castle.” Persuasions 7 (1985): 78-81. https://jasna.org/persuasions/printed/number7/lane.html

Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen’s Country Life. London: Frances Lincoln, 2014.

Loudon, John Claudius An Encyclopædia of Gardening: Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape Gardening. London: Longman. 1835. Reprinted in The English Landscape Garden Series, Ed. John Dixon Hunt, Garland Publishing, NY. 1982. Print. Digitized by the University of Michigan: Loudon’s Encyclopedia of Gardening

Marshall, William Planting and Ornamental Gardening: A Practical Treatise, 1785 first edition London J. Dodsley (The first edition was owned by Edward Austen Knight). Digitized by The British Library: Marshall’s Planting and Ornamental Gardening

Meader, James. The Planter’s Guide Or, Pleasure Gardener’s Companion. Giving Plain Directions, with Observations, for the Proper Disposition and Management of the Various Trees and Shrubs for a Pleasure Garden Plantation. London: G. Robinson, 1779. Digitized by the U. of Michigan: Meader’s Planter’s Guide

Miller, Philip. The Gardeners Kalendar, Fifteenth Ed. London: J. Rivington, Pub, 1769. Digitized by Oxford U: Miller’s Gardener’s Kalendar (The first edition of 1732 was in Knight collection at Godmersham.)

Natali, Christopher J. “Was Northanger Abbey’s General Tilney Worth His Weight in Pineapples?” Persuasions On-Line 40.1 (2019). https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/volume-40-no-1/natali/.

Repton, Humphry. Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816), Print version in The English Landscape Garden Series. Ed. John Dixon Hunt, Garland Publishing, NY, 1982. Digital version available in The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphrey Repton, Esq Being His Entire Works on These Subjects. Ed. J C Loudon, 1840. Digitized by the U. of Michigan: Repton’s Complete Works

Repton, Humphry. The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphrey Repton, Esq Being His Entire Works on These Subjects Ed. J C Loudon, 1840. Digitized by the U. of Michigan: Repton’s Complete Works

Repton, Humphry. Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803). Available in The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphrey Repton, Esq Being His Entire Works on These Subjects. Ed. J C Loudon, 1840. Digitized by U. of Michigan: Repton’s Complete Works

Wilson, Kim. In the Garden with Jane Austen. London: Frances Lincoln, 2008.